Studies show there have been more incidents of violence against teachers. An American Psychological Association (APA) survey of nearly 15,000 school staff shows almost 60% of teachers feel victimized in some way at work.

Experts on the APA task force that conducted the study recommended improving teacher education programs so that there is more focus on managing student behavior, in addition to providing social emotional learning training for all school staff. The task force also backed the Comprehensive Mental Health In Schools Pilot Program Act which supports restorative justice as a social emotional learning technique to strengthen relationships between students, teachers and school leaders. But as can often be the case with recommendations – whether through lack of funding, will or support, for example – schools fall short.

“We have seen behaviors at a level that we’ve never experienced before at my high school,” Marta Schaffer, an English teacher in Oroville, California, told me earlier this year. “There’s been fighting pretty much every week, aggression towards staff and teachers and fighting happening in classrooms.”

Schaffer says there are four social workers to meet with students at the three schools in her district and no restorative justice programs. With limited mental health resources, student behavior during the first year in person after pandemic distance learning had been erratic and unpredictable.

What is restorative justice?

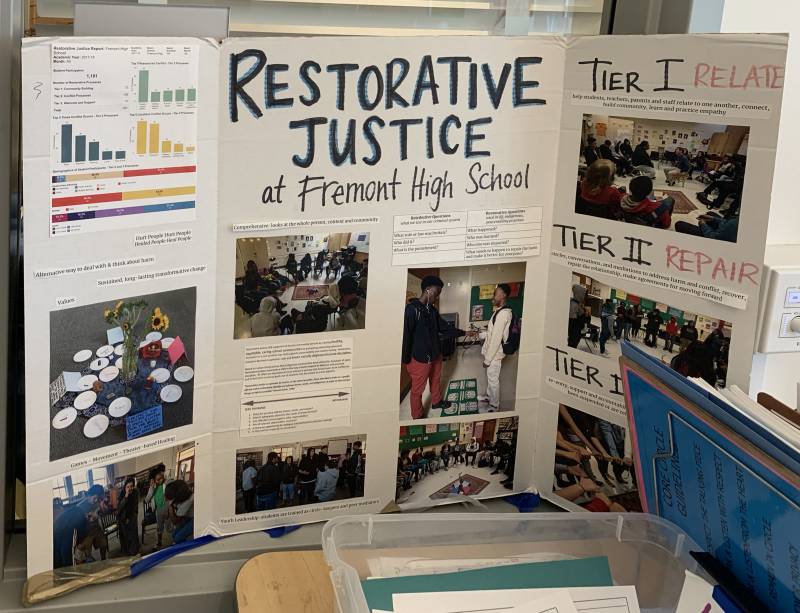

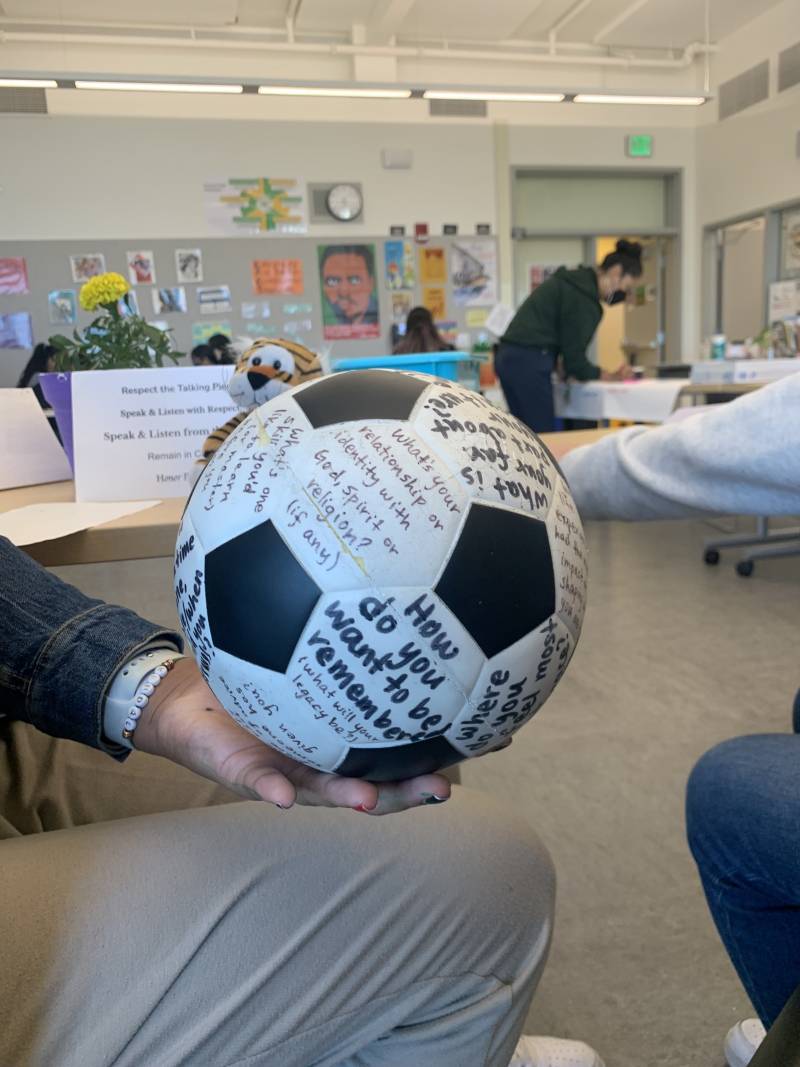

Restorative justice (RJ) programs are small talking groups called circles – because of how people are seated around one another – used to build community and respond to conflict. One person speaks at a time and everybody gets a chance to speak or pass.

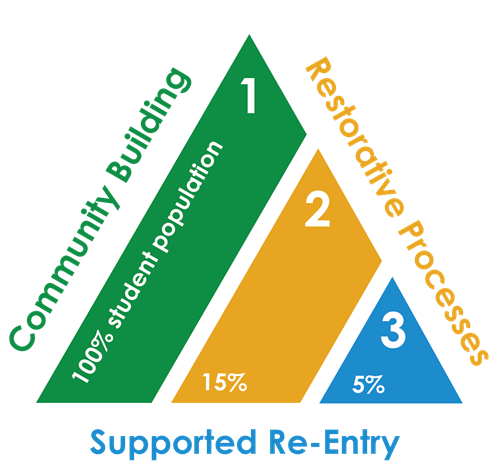

RJ circles are composed of three tiers: Tier one circles focus on building and maintaining community; they are meant to build relationships, so that conflict is less likely to happen. When a conflict arises, a tier two circle is done to address and repair harm. Tier three circles provide individualized support for someone coming back into the community. “It could be a student, teacher, or someone coming in from being incarcerated. We want to identify what they need to be successful and help them get that,” says Yusem.

OUSD has had RJ since 2007 and in 2017, they invested $2.5 million in their RJ programs. Yusem works with facilitators based in middle schools and high schools across the district. He says the facilitator’s goal is to “create an environment where teaching and learning can happen, where it feels safe, welcoming, where social and emotional learning can take place and students can begin to access the part of their brain they need to learn.”

OUSD had built a strong foundation with restorative justice practices when the pandemic forced students and teachers into lockdown. They continued to do RJ circles online to support students. “We would do circles for people impacted by COVID,” says Yusem. “They were for people who either got sick themselves or had to take care of a loved one or lost a loved one.”

Restorative justice in the classroom

When students returned in person, Tatiana Chaterji, the RJ facilitator at Kimberly Higareda’s school, had to do a lot of work to help students feel comfortable around each other again. In OUSD, all ninth graders are required to take her RJ leadership class at least once. “RJ is all about relationships, and I think relationships have been weaker,” says Chaterji about her students. Because students haven’t seen each other in a while, some conflicts have been festering for years and may have gotten worse because of social media.

“My day-to-day looks like a lot of training, teaching and introducing empathy,” says Chaterji. “Trauma, neglect, youth, social media, ego and all the sort of negative forces that encourage us to be so self-centered take us away from caring about others.”

RJ helped Higareda keep in touch with her peers during distance learning. While her online classes were “dead silent,” people talked during online RJ circles even if they kept their videos off. “I definitely think it helped me because I knew names and I knew voices. Without that, I wouldn’t have known anyone,” says Higareda. Even though she kept in contact with some peers through online RJ circles, Higareda says her in-person relationships with classmates were strained.

For instance, in her RJ leadership class, there was tension between upperclassmen and underclassmen. Higareda and other juniors felt the younger students were not pulling their weight on projects and activities. “We were friends with each other and not them,” says Higareda. “At moments we yelled at each other. I saw a couple of people yelling at each other really bad words and comments,” she says. The class did a tier two circle to deal with the conflict.

Higareda is the oldest in her household, so when it was her turn to speak she told her classmates that she was tired of being a leader all the time; she wanted others to take initiative and contribute to the class community.

“That circle opened up this space for us to talk and voice our opinions and it was great after. We all learned something new,” says Higareda. After the circle cleared things up, students who weren’t on speaking terms earlier in the year were following each other on social media and hanging out outside of class.

“We’re all going through so much,” says Kimberly. “I’ve done so many circles where people actually get more vulnerable and I see them for something more than they express to be.”

An ecosystem of care

School districts in Santa Ana, San Diego and Los Angeles have invested in RJ programs. “There’s still a huge movement to adopt these practices in schools,” says Andrew Martinez, another member of the APA task force on violence against teachers.

Martinez studied the effect of RJ programs in New York schools. The research spanned two years and set out to see whether RJ could reduce suspensions. Based on his interviews with over 80 students, he found that RJ programs strengthened students’ relationships with the school, but did not reduce suspensions. That could be because suspensions have as much to do with adult decisions as they do with student behavior.

“The science behind restorative justice practices within school settings has kind of lagged,” says Martinez. Without research and numbers to back up RJ’s success, it’s hard to push for funding RJ programs at schools.

Even still, Martinez sees similarities between how teachers used RJ circles to navigate the community violence in New York public schools and how RJ is being used to address poverty, loss and inequity after the pandemic. “It created a space to hear about a lot of concerning things happening in the lives of children,” says Martinez.

He recommends that RJ is part of an ecosystem of care at a school. Once caring adults know what students are going through, they can give them referrals to additional support like psychologists, social workers and counselors.