CNN

—

You probably associate Labor Day with sales, family barbecues and the unofficial end of summer.

For most Americans, the long weekend is a much-needed opportunity to reconnect with friends and family and provides a last hurrah before the start of fall.

But Monday’s holiday holds a much deeper meaning, rooted in the 19th century fight for fair working conditions. Labor Day was originally designed to honor workers as part of the American organized labor movement.

Labor Day was first celebrated unofficially by labor activists and individual states in the late 1800s, according to the US Department of Labor. New York was the first state to introduce a bill recognizing Labor Day, but Oregon was the first to actually codify it into law in 1887. Colorado, Massachusetts, New Jersey and New York had followed suit by the end of 1887.

Joshua Freeman, a labor historian and professor emeritus at the City University of New York, tells CNN that the holiday developed as unions were beginning to strengthen again after the 1870s recession.

In New York City, two events converged that contributed to the formation of Labor Day, Freeman says. First, the now-defunct Central Labor Union was formed as a “umbrella body” for unions across trades and ethnic groups. Additionally, the Knights of Labor, then the largest national labor convention, held a convention in the city, complete with a large parade. But the parade fell on a Tuesday at the start of September – and many workers were unable to attend.

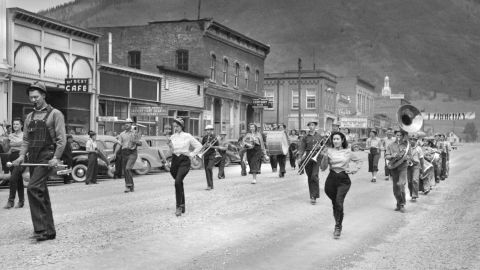

The convention was a huge success, and unions around the country started holding their own labor celebrations at the start of September, usually on the first Monday of the month.

At the beginning, “it was a somewhat daring move to participate, because you could get yourself fired,” Freedman said. But over time, states began to recognize the holiday, and it became more common for employers to give their employees the day off.

It wasn’t until June 28, 1894 that Congress passed an act naming the first day of September a legal holiday called Labor Day.

Freeman says that earlier that year, President Grover Cleveland sent in the military to squash the Pullman railway strike. Cleveland pushed through legislation to recognize Labor Day just days after the strike ended, in a “gesture towards organized labor,” Freeman said.

At the time Labor Day was formed, unions were fighting for “very specific improvements in their working conditions,” Freeman said. Workers were fighting hard for the eight-hour work day most workers enjoy today. And Labor Day was an opportunity for them to come together to discuss their priorities – and for the country to acknowledge the contributions workers make to society.

But there was also a more radical political thread to the Labor Day celebration, Freeman says. The Knights of Labor were exploring the idea that “what we call the capitalist or industrial system was fundamentally exploitative,” he said. “It introduced kind of inequities and inequalities, not just in wealth, but also in power. So they wanted a greater say in society for working people.”

“Back when Labor Day began, there were a lot of voices that were fundamentally challenging this emerging system,” Freeman added. Labor leaders at the time advocated for alternatives to the “capitalist wage system,” like collective ownership of corporations or socialism.

Over time, the radical politics around Labor Day became tempered. Around the world, most countries honor workers with a holiday called May Day, celebrated on May 1, which also has its origins in the late 19th century and the fight for the eight-hour work day. For a long time, Freeman says, Americans celebrated both May Day and Labor Day.

But eventually, Labor Day began to be seen as the more “moderate” of the two holidays, in comparison to May Day, which was originally established by the Marxist International Socialist Congress.

“By the turn of the 20th century, calls for transforming American life, they pretty much disappear from Labor Day,” Freeman said. “As more and more employers began to give all their workers the day off, it became less associated specifically with unions.”

After World War II, Labor Day celebrations had a brief revival, especially in cities like Detroit and New York City. But by the 60s and 70s, they had tapered off again.

“I think most people just think of as the end of summer holiday,” Freeman said. “It’s not really associated with its origins that much.”

You might have heard the outdated rule that you shouldn’t wear white after Labor Day.

But don’t worry: There’s no fashion police out there waiting to see if you don a white shirt in September. And the idea actually has a pretty problematic origin.

The rule was one of many 19th century style customs used to distinguish the upper and middle classes, according to Valerie Steele, a fashion historian and director of The Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology.

“As you got more and more sort of ordinary people, whether middle class or lower middle class, being able to have enough money to try to dress fashionably, then there become more rules so that the more upper class people can say ‘yes, but you’re doing it wrong,’” Steele told CNN.

White was tied to summer vacations – a privilege only few could afford. Labor Day represented the “reentry” into city life and the retirement of white summer clothes after a summer of leisure for the upper classes, Steele says.

But the arbitrary rule all but disappeared during the 1970s, Steele says. The 1960s “Youthquake” allowed young people to challenge old stylistic norms, including the Labor Day rule.

“It was part of a much wider anti-fashion movement,” said Steele.