Let’s see how to do it in stages: we start with the following test that

tries to compile the template. In Go we use the standard html/template package.

Go

func Test_wellFormedHtml(t *testing.T) {

templ := template.Must(template.ParseFiles("index.tmpl"))

_ = templ

}

In Java, we use jmustache

because it’s very simple to use; Freemarker or

Velocity are other common choices.

Java

@Test

void indexIsSoundHtml() {

var template = Mustache.compiler().compile(

new InputStreamReader(

getClass().getResourceAsStream("/index.tmpl")));

}

If we run this test, it will fail, because the index.tmpl file does

not exist. So we create it, with the above broken HTML. Now the test should pass.

Then we create a model for the template to use. The application manages a todo-list, and

we can create a minimal model for demonstration purposes.

Go

func Test_wellFormedHtml(t *testing.T) {

templ := template.Must(template.ParseFiles("index.tmpl"))

model := todo.NewList()

_ = templ

_ = model

}

Java

@Test

void indexIsSoundHtml() {

var template = Mustache.compiler().compile(

new InputStreamReader(

getClass().getResourceAsStream("/index.tmpl")));

var model = new TodoList();

}

Now we render the template, saving the results in a bytes buffer (Go) or as a String (Java).

Go

func Test_wellFormedHtml(t *testing.T) {

templ := template.Must(template.ParseFiles("index.tmpl"))

model := todo.NewList()

var buf bytes.Buffer

err := templ.Execute(&buf, model)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

}

Java

@Test

void indexIsSoundHtml() {

var template = Mustache.compiler().compile(

new InputStreamReader(

getClass().getResourceAsStream("/index.tmpl")));

var model = new TodoList();

var html = template.execute(model);

}

At this point, we want to parse the HTML and we expect to see an

error, because in our broken HTML there is a div element that

is closed by a p element. There is an HTML parser in the Go

standard library, but it is too lenient: if we run it on our broken HTML, we don’t get an

error. Luckily, the Go standard library also has an XML parser that can be

configured to parse HTML (thanks to this Stack Overflow answer)

Go

func Test_wellFormedHtml(t *testing.T) {

templ := template.Must(template.ParseFiles("index.tmpl"))

model := todo.NewList()

// render the template into a buffer

var buf bytes.Buffer

err := templ.Execute(&buf, model)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

// check that the template can be parsed as (lenient) XML

decoder := xml.NewDecoder(bytes.NewReader(buf.Bytes()))

decoder.Strict = false

decoder.AutoClose = xml.HTMLAutoClose

decoder.Entity = xml.HTMLEntity

for {

_, err := decoder.Token()

switch err {

case io.EOF:

return // We're done, it's valid!

case nil:

// do nothing

default:

t.Fatalf("Error parsing html: %s", err)

}

}

}

This code configures the HTML parser to have the right level of leniency

for HTML, and then parses the HTML token by token. Indeed, we see the error

message we wanted:

--- FAIL: Test_wellFormedHtml (0.00s)

index_template_test.go:61: Error parsing html: XML syntax error on line 4: unexpected end element

In Java, a versatile library to use is jsoup:

Java

@Test

void indexIsSoundHtml() {

var template = Mustache.compiler().compile(

new InputStreamReader(

getClass().getResourceAsStream("/index.tmpl")));

var model = new TodoList();

var html = template.execute(model);

var parser = Parser.htmlParser().setTrackErrors(10);

Jsoup.parse(html, "", parser);

assertThat(parser.getErrors()).isEmpty();

}

And we see it fail:

java.lang.AssertionError: Expecting empty but was:<[<1:13>: Unexpected EndTag token [] when in state [InBody],

Success! Now if we copy over the contents of the TodoMVC

template to our index.tmpl file, the test passes.

The test, however, is too verbose: we extract two helper functions, in

order to make the intention of the test clearer, and we get

Go

func Test_wellFormedHtml(t *testing.T) {

model := todo.NewList()

buf := renderTemplate("index.tmpl", model)

assertWellFormedHtml(t, buf)

}

Java

@Test

void indexIsSoundHtml() {

var model = new TodoList();

var html = renderTemplate("/index.tmpl", model);

assertSoundHtml(html);

}

Level 2: testing HTML structure

What else should we test?

We know that the looks of a page can only be tested, ultimately, by a

human looking at how it is rendered in a browser. However, there is often

logic in templates, and we want to be able to test that logic.

One might be tempted to test the rendered HTML with string equality,

but this technique fails in practice, because templates contain a lot of

details that make string equality assertions impractical. The assertions

become very verbose, and when reading the assertion, it becomes difficult

to understand what it is that we’re trying to prove.

What we need

is a technique to assert that some parts of the rendered HTML

correspond to what we expect, and to ignore all the details we don’t

care about. One way to do this is by running queries with the CSS selector language:

it is a powerful language that allows us to select the

elements that we care about from the whole HTML document. Once we have

selected those elements, we (1) count that the number of element returned

is what we expect, and (2) that they contain the text or other content

that we expect.

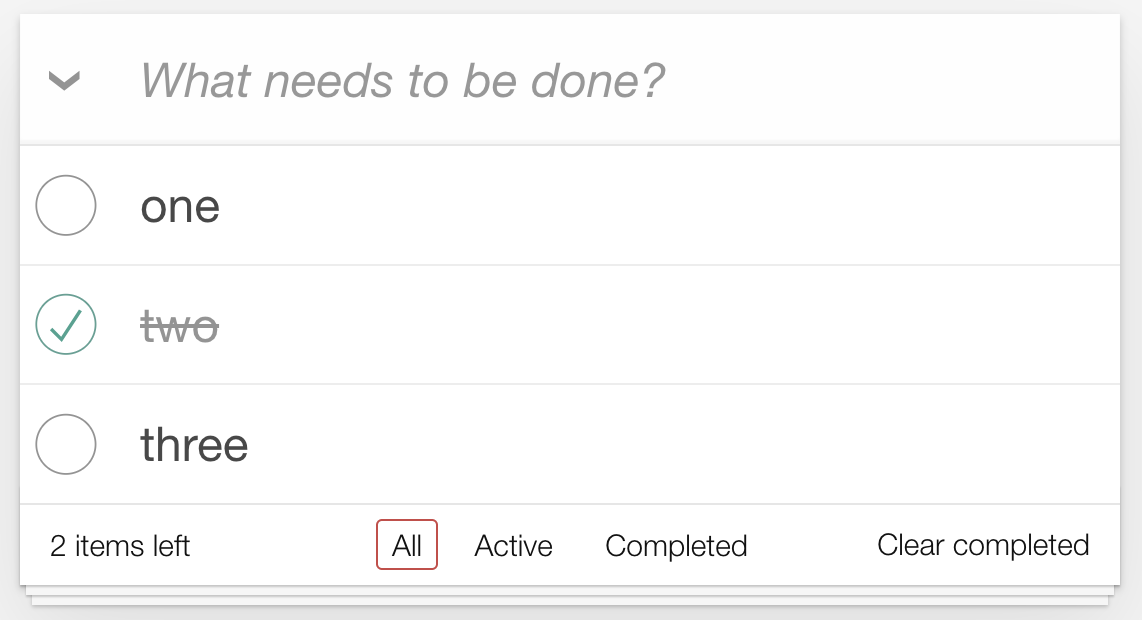

The UI that we are supposed to generate looks like this:

There are several details that are rendered dynamically:

- The number of items and their text content change, obviously

- The style of the todo-item changes when it’s completed (e.g., the

second) - The “2 items left” text will change with the number of non-completed

items - One of the three buttons “All”, “Active”, “Completed” will be

highlighted, depending on the current url; for instance if we decide that the

url that shows only the “Active” items is/active, then when the current url

is/active, the “Active” button should be surrounded by a thin red

rectangle - The “Clear completed” button should only be visible if any item is

completed

Each of this concerns can be tested with the help of CSS selectors.

This is a snippet from the TodoMVC template (slightly simplified). I

have not yet added the dynamic bits, so what we see here is static

content, provided as an example:

index.tmpl