Any large software effort, such as the software estate for a large

company, requires a lot of people – and whenever you have a lot of people

you have to figure out how to divide them into effective teams. Forming

Business Capability Centric teams helps software efforts to

be responsive to customers’ needs, but the range of skills required often

overwhelms such teams. Team Topologies is a model

for describing the organization of software development teams,

developed by Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais. It defines four forms

of teams and three modes of team

interactions. The model encourages healthy interactions that allow

business-capability centric teams to flourish in their task of providing a

steady flow of valuable software.

The primary kind of team in this framework is the stream-aligned

team, a Business Capability Centric team that is

responsible for software for a single business capability. These are

long-running teams, thinking of their efforts as providing a software

product to enhance the business capability.

Each stream-aligned team is full-stack and full-lifecycle: responsible for

front-end, back-end, database,

business analysis, feature prioritization,

UX, testing, deployment, monitoring – the

whole enchilada of software development.

They are Outcome Oriented, focused on business outcomes rather than Activity Oriented teams focused on a function such as business

analysis, testing, or databases.

But they also shouldn’t be too

large, ideally each one is a Two Pizza Team. A large

organization will have many such teams, and while they have different

business capabilities to support, they have common needs such as data

storage, network communications, and observability.

A small team like this calls for ways to reduce their cognitive load, so they

can concentrate on supporting the business needs, not on (for example) data

storage issues. An important part of doing this is to build on a platform

that takes care of these non-focal concerns. For many teams a platform can

be a widely available third party platform, such as Ruby on Rails for a

database-backed web application. But for many products there is no

single off-the-shelf platform to use, a team is going to have to find and

integrate several platforms. In a larger organization they will have to

access a range of internal services and follow corporate standards.

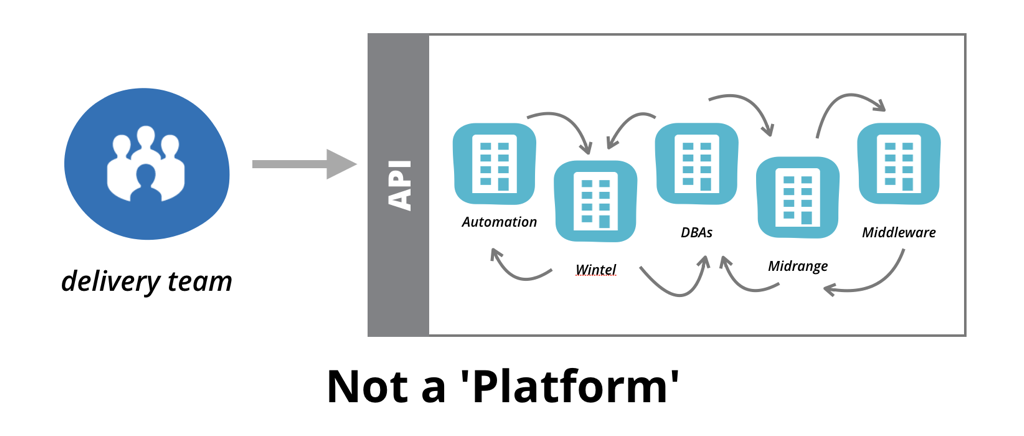

What I Talk About When I Talk About Platforms

These days everyone is building a ‘platform’ to speed up delivery of

digital products at scale. But what makes an effective digital platform? Some

organisations stumble when they attempt to build on top of their existing

shared services without first addressing their organisational structure and

operation model.

This problem can be addressed by building an internal platform for the

organization. Such a platform can do that integration of third-party

services, near-complete platforms, and internal services. Team Topologies

classifies the team that builds this (unimaginatively-but-wisely) as a platform

team.

Smaller organizations can work with a single platform team, which

produces a thin layer over an externally provided set of products. Larger

platforms, however, require more people than can be fed with two-pizzas.

The authors are thus moving to describe a platform grouping

of many platform teams.

An important characteristic of a platform is that it’s designed to be used

in a mostly self-service fashion. The stream-aligned teams are still

responsible for the operation of their product, and direct their use of the

platform without expecting an elaborate collaboration with the platform team.

In the Team Topologies framework, this interaction mode is referred to as

X-as-a-Service mode, with the platform acting as a service to the

stream-aligned teams.

Platform teams, however, need to build their services as products

themselves, with a deep understanding of their customer’s needs. This often

requires that they use a different interaction mode, one of collaboration

mode, while they build that service. Collaboration mode is a more

intensive partnership form of interaction, and should be seen as a temporary

approach until the platform is mature enough to move to x-as-a service

mode.

So far, the model doesn’t represent anything particularly inventive.

Breaking organizations down between business-aligned and technology support

teams is an approach as old as enterprise software. In recent years, plenty

of writers have expressed the importance of making these business capability

teams be responsible for the full-stack and the full-lifecycle. For me, the

bright insight of Team Topologies is focusing on the problem that having

business-aligned teams that are full-stack and full-lifecycle means that

they are often faced with an excessive cognitive load, which works against

the desire for small, responsive teams. The key benefit of a

platform is that it reduces this cognitive load.

A crucial insight of Team Topologies is that the primary benefit of a

platform is to reduce the cognitive load on stream-aligned

teams

This insight has profound implications. For a start it alters how

platform teams should think about the platform. Reducing client teams’

cognitive load leads to different design decisions and product roadmap to

platforms intended primarily for standardization or cost-reduction.

Beyond the platform this insight leads Team Topologies to develop their model

further by identifying two more kinds of team.

Some capabilities require specialists who can put considerable time and

energy into mastering a topic important to many stream-aligned teams. A

security specialist may spend more time studying security issues and

interacting with the broader security community than would be possible as a

member of a stream-aligned team. Such people congregate in enabling

teams, whose role is to grow relevant skills inside other teams

so that those teams can remain independent and better own and evolve their

services.

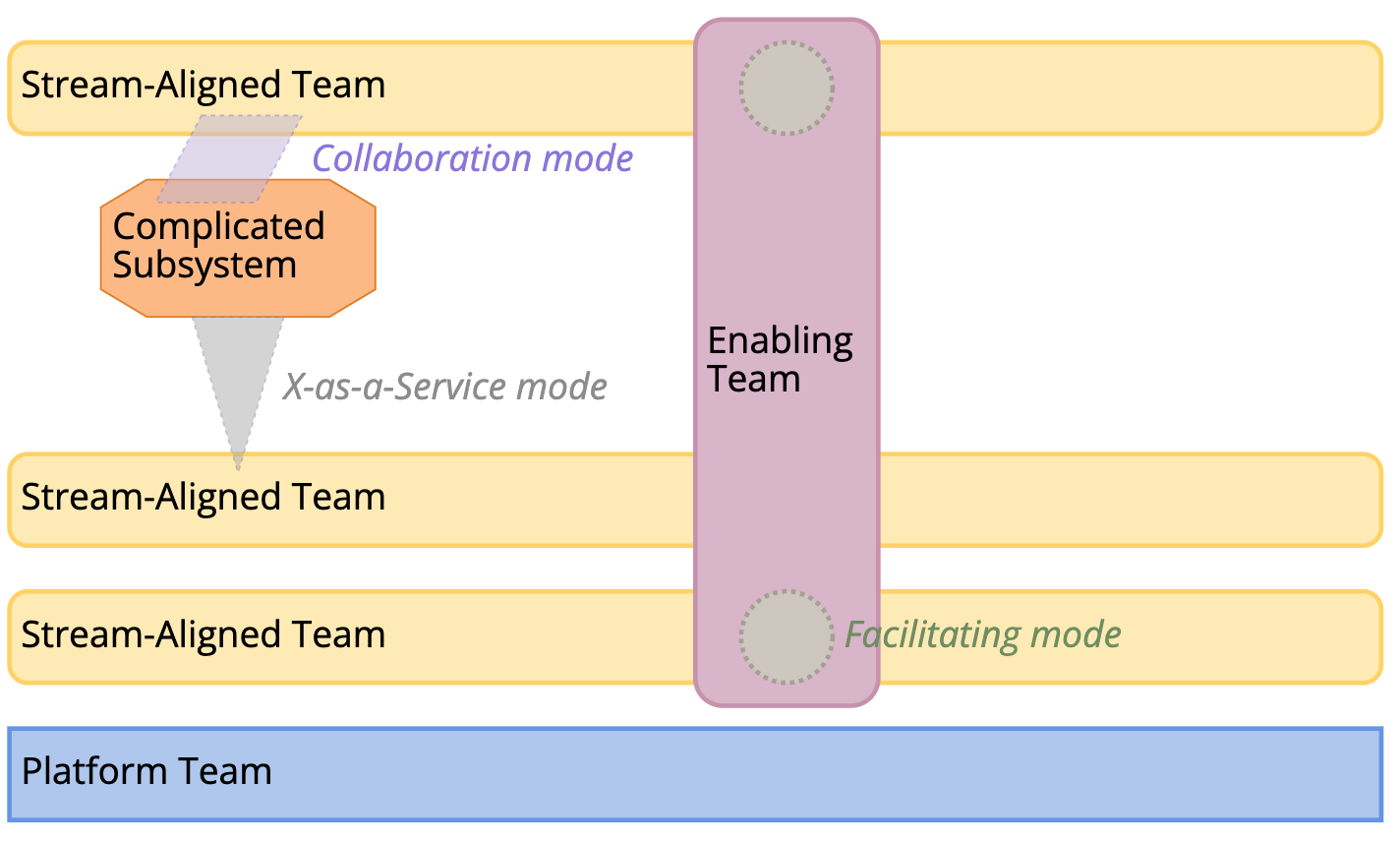

To achieve this enabling teams primarily use the third and final interaction

mode in Team Topologies. Facilitating mode

involves a coaching role, where the enabling team isn’t there to write and

ensure conformance to standards, but instead to educate and coach their colleagues so

that the stream-aligned teams become more autonomous.

Stream-aligned teams are responsible for the whole stream of value for their

customers, but occasionally we find aspects of a stream-aligned team’s work

that is sufficiently demanding that it needs a dedicated group to focus on

it, leading to the fourth and final type of team:

complicated-subsystem team. The goal of a complicated-subsystem

team is to reduce the cognitive load of the stream-aligned teams that use

that complicated subsystem. That’s a worthwhile division even if there’s

only one client team for that subsystem. Mostly complicated-subsystem teams strive to interact

with their clients using x-as-a service mode, but will need to

use collaboration mode for short periods.

Team Topologies includes a set of graphical symbols to illustrate teams

and their relationships. These shown here are from the current standards, which differ from those used in

the book. A recent article elaborates on

how to use these diagrams.

Team Topologies is designed explicitly recognizing the influence of

Conways Law. The team organization that it encourages

takes into account the interplay between human and software organization.

Advocates of Team Topologies intend its team structure to shape the future

development of the software architecture into responsive and decoupled

components aligned to business needs.

George Box neatly quipped: “all models are wrong, some are useful”. Thus

Team Topologies is wrong: complex organizations cannot be

simply broken down into just four kinds of teams and three kinds of

interactions. But constraints like this are what makes a model useful. Team

Topologies is a tool that impels people to evolve their organization into a more effective

way of operating, one that allows stream-aligned teams to maximize their

flow by lightening their cognitive load.

Acknowledgements

Andrew Thal, Andy Birds, Chris Ford, Deepak

Paramasivam, Heiko Gerin, Kief Morris, Matteo

Vaccari, Matthew Foster, Pavlo Kerestey, Peter Gillard-Moss, Prashanth Ramakrishnan, and Sandeep Jagtap discussed drafts of this post on our internal mailing

list, providing valuable feedback.

Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais kindly provided detailed comments on this post,

including sharing some of their recent thinking since the book.

Further Reading

The best treatment of the Team Topologies framework is the book of the same name, published in 2019. The authors

also maintain the Team Topologies website

and provide education and training services. Their recent article on team interaction modeling is a good intro to

how the Team Topologies (meta-)model can be used to build and evolve a

model of an organization.

Much of Team Topologies is based on the notion of Cognitive Load. The

authors explored cognitive load in Tech Beacon. Jo Pearce expanded on how

cognitive load may apply to software

development.

The model in Team Topologies resonates well with much of the thinking

on software team organization that I’ve published on this site. You can

find this collected together at the team

organization tag.