*This is an article from the Winter 2022 issue of Contentment Magazine.

By Jeff Jernigan, PhD, FAIS

The class was getting frustrated. Every answer they gave was shot down by me. Little did they realize this was an intentionally created readiness learning moment. Or at least I hoped it would be. There were three points to make: our tendency is to make things too complicated; we look for absolute solutions first without sufficient reflection; and (if I could get them worked up enough) our own frustration at not coming up with the correct answer narrows and clouds our own thinking. The right answer to the question is SLEEP. Now, we can go back to the beginning where the question was first asked.

This was a neurobiology class for soon-to-be professional counselors, coaches, and therapists. The question was simple, “Given the following symptoms, what is wrong with this client?” Here are the symptoms: discouragement, anxiety, tunnel vision, cloudy thinking, memory loss, poor decision making, emotional variability, paranoia, exaggerated startle response, fatigue, loss of some motor control, and a mysterious rash. The answers ranged from Lime Disease to Lupus to a number of sophisticated disorders. Fortunately, the client had a history of lack of sleep, interrupted sleep, and inability to sleep… all of which explain this constellation of symptoms.

The client’s problem is not unusual. Insufficient sleep has an estimated economic impact of over $411B each year in the United States1 35% of all adults in the US report on average sleeping less than seven hours per night.2 Less sleep means less physical and mental health.3 What is it we need to understand about the biology of sleep that can help us sustain physiological and psychological health? Here are some mind and body basics we should consider first when we share many of the same symptoms as the client above.

Sleep is a complex result of genetic, biological, and cellular interaction and involves a number of structures in the brain.4 These include the basal forebrain, thalamus, and hypothalamus which are involved in regulating sleep responding to signals between multiple structures in the brain.5 No need to remember these names. Just think of the worst concentration of freeway overpasses, on-ramps, off-ramps, and signage stacked in multiple layers in any major metropolitan city and you will get the idea. Lots of things impact sleep. At this point, just keep in mind that the brain is key to everything.

Nutrition, exercise, and sleep are vital to good brain health. Without a healthy brain, sleep will run away from you like night runs away from a sunrise. There are a lot of things that can interrupt sleep: getting up to attend a child, nightmares, a loud noise in the house or outside that bears investigation, an upset stomach, sports injury, or the neighbor’s late-night party. These are natural interruptions that can be a nuisance but don’t necessarily affect your health negatively. Poor nutrition, insufficient exercise, and lack of sleep due to other causes like worry, anxiety, stress, and trauma can and do cause sleep problems.

Most of the neurotransmitters our brain needs for optimal operation are produced from the food we eat.6 Exercise produces an enzyme which triggers a brain clean-up function only while we sleep.7 Interrupted sleep and lack of sleep impairs this biological process and produces foggy-headed cognition as a result. Neurotransmitters that enable the different structures of the brain to communicate with each other are produced in our gut.8 The most important part of the brain regulating sleep duration is the hypothalamus.9 The results of a poor diet over time and lack of regular exercise decrease the ability of the hypothalamus to promote sleep.10 Our mind and body are interactively engaged when it comes to sleeping well. Sleep seems so natural that many are surprised at so many factors must come together in the right way at the right time for a good night’s sleep.

There are other causes for poor sleep besides a poor diet and lack of exercise: nightmares not attributed to physical cause like loud noises, too much pizza, or pain; interruptions of the Circadian Rhythm; and moral stress in the present and/or moral injury in the past. We will look at each of these categories next. A note of caution here: if your nutrition, exercise, and sleep patterns are messed up, it may be difficult to determine if any of these non-physical causes of sleep problems are at fault. Often, sleep problems are a set of interrelated factors, both biological and psychological, that need to be understood.

Dreams are a natural product of our physiology and psychology, playing a healthy role in our lives.11 Dreams can be responses to our external environment. For example, a noise heard in the night that does not fully awaken us but requires a rational explanation may be processed in a dream. Dreams can also be a response to our internal environment: too much pepper on too much pizza that we had for dinner that is now talking back to us with discomfort. Again, it is a physical stimulus for which our minds require an explanation, using imagination and creativity to produce an answer. Dreams are also a mechanism for working out solutions to problems while we sleep.

Often, our subconscious mind shifts into problem-solving mode while we sleep but is missing a few pieces of the puzzle. When we sleep problem-solving can be more difficult than in awake states because working memory (where conscious thought occurs) must access short term and long-term memory, as well as other functions in our brain that may be off-line. When there is a mix-up, our mind will borrow a bit of recollection from something else and slip it into the empty spot it is trying to fill.12 This can create some very interesting associations in our dreams. This hiccup in trying to rationalize our thoughts while sleeping happens because our brains work differently, in some respects, while we are asleep. Some functions in our brain go into their own sleep mode like our computers do when we don’t want to shut them down entirely. For example, while we sleep and dream, our brains are working without the benefit of our logic filter.13 This can certainly make for some spectacular as well as disturbing dreams that wake us up as our subconscious looks for solutions.

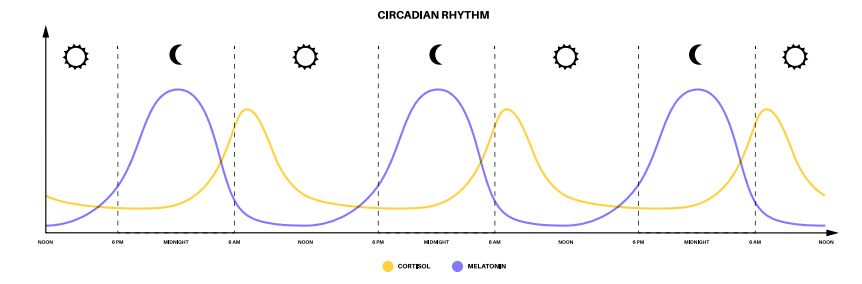

The Circadian Rhythm is a label for physical, mental, and behavioral changes that follow a twenty-four-hour cycle. The rhythm we are interested in most, as it affects sleep, involves daylight and darkness.14 Our brain senses the blue light spectrum our eyes see when we look at the sky. When night falls, our brain senses the absence of this spectrum and begins to produce melatonin which helps induce sleep. Yes, this is a term you are familiar with! Melatonin is available as an over-the-counter sleep aid available at pharmacies as well. Now, I realize at this moment we are talking about something physical going on in our bodies. Bear with me, I will get to the all-important non-physical point in a moment.

Our smart phone screens, tablet screens, and televisions also emit this same light spectrum. So, if you are staying up late watching television, gaming on your tablet, or texting your friends late into the night your brain isn’t producing any melatonin. You won’t fall asleep until you are literally exhausted, which is too late to get the full benefit of the eight hours of sleep every adult needs. Easy solution: turn your devices off one hour before bedtime. If you need additional help, read something; a magazine, book, your mail, anything that that does not require a digital device. You can also get screens for phones, tablets and laptops that filter out this spectrum as well.

Here is the non-physical aspect of this problem. We cannot change the orbit of the earth and therefore the rising and setting of the sun. However, we can change our habits that are getting in the way of a good night’s sleep. Otherwise, we must agree to accept the risk of disease inherent in lack of sleep.15 Insufficient sleep has been linked to higher risk for developing Type 2 Diabetes. Sleep disturbance has been linked to higher risk for cardiovascular disease. Interrupted sleep has been linked to higher risk for obesity. The relationship between depression and sleep is complex with back-and-forth evidence of depression interrupting sleep and sleep interruptions worsening depression. I really like Winnie the Pooh’s advice when it comes to sleep, “When all else fails, take a nap.”16 You can catch up on sleep you miss.

There are two very common but seldom recognized sources of sleep disturbance. These two conditions emerge into our consciousness ever so slowly and go unnoticed until they can no longer be ignored: moral distress and moral injury. When they do surface in our awareness most of us do not have a name for them and shunt them aside as bad feelings that should be ignored.

Moral distress is a psychological phenomenon quite different from ethical dilemmas or emotional distress.17 Moral distress occurs in an environment when one knows the right thing to do, but constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action.18 This can occur in any situation where decisions, or indecision, are constrained by established requirements or overruled by others. The most common arena for this to occur is the workplace where institutional requirements are overruled by more senior leaders. This can also occur in relationships where social or cultural norms and values are violated by others, and no one does anything about it. An example would be observing someone being verbally or physically abused and no one says or does anything about it out of fear of reprisals, avoidance (it is none of my business), embarrassment, or simply not knowing what to do. It leaves us with a moral dilemma we would rather avoid and forget. We move away from those kinds of incidents carrying the stress created with us. Enough of this can lead to moral injury.

A moral injury can occur in response to acting or witnessing behaviors that go against an individual’s values and moral beliefs which erode self-esteem and confidence, breaking down long and strongly held beliefs about themselves and the world they live in. The result is disillusionment, despair, and eventual physiological and psychological burnout. It is like an iceberg which can sink anyone’s boat and is not getting much attention.

Sources of moral distress and injury can vary widely. For example, care providers taking care of children or aging adults in their homes or institutions can develop compassion fatigue as a result of unending pressure to be engaged in caregiving without appropriate relief. We feel responsible, committed, and guilty or ashamed when it gets hard enough to quit. Our personal values and inability to hold up under pressure physically and emotionally are in constant conflict and we burnout. Or requirements to return to the office conflict with realities of living with a pandemic and your employer doesn’t provide remote working options. Or, corners are cut, safety is ignored, and quality control is no longer enforced on the production line to the point you know if you speak up you will be out of a job. When we sleep our subconscious wrestles with these feelings enough to disturb our sleep, waking us up, often with feelings of guilt and shame we may not be able to attribute to anything specific.

If this is your experience, there is much hope! The first step is to recognize the situation for what it is and is not. It is an assault on your sense of right and wrong. It is not a judgment of who you are as a person. Consider what you can change and what you cannot change. You probably are not responsible for what you just experienced. You may need to think through or get some advice about what you should do if you encounter this experience again. Release what you cannot control and respond to what you can control. You may need to reframe an issue to view it in a different way. Instead of thinking, “Well, I cannot do anything about that!” reconsider what you may be able to do, perhaps beginning with identifying who you can talk to that has good judgment about these kinds of dilemmas. Actively decide to be ready for what life puts in your way so that you know how to respond inwardly and what action, if any, to take walking away from a morally distressing experience.

The most significant preventative measure you can take to help ensure healthy sleep patterns is building and sustaining resilience. Resilience is a cumulative result of several elements working together. Leave something out, and you will not get the desired result. These are not new factors: good nutrition, sufficient exercise, and sleeping at least eight hours a day. Add to that meaningful relationships and purposeful work and you will minimize the impact of any moral distress you may experience. When the obvious has been considered and discarded, discovering why you are not sleeping well can be very confusing. It is like my life coach, Winnie the Pooh, says, “I am not lost, for I know where I am. But however, where I am may be lost.”19 Look at the big picture: physical health, mental wellness, good friends, and work that is important to you and you may just come up with a new revelation about where you really are and know what to do.

References

- Suni, E., Troung, K., Statistics About the Impact of Insufficient Sleep: The Sleep Foundation, How Sleep Works: Understanding the Science of Sleep, May 2022

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Falup-Pecurariu, C., Diaconu, S., et al, Neurobiology of Sleep (Review): Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 21(3) March 2021

- Ibid

- Jernigan, J., Physical Ramifications of Prolonged Stress: Contentment Magazine, American Institute of Stress, Fall 2020

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Seigel, J., The Neurotransmitters of Sleep: Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 16(Suppl 16), 2004

- Ibid

- Jernigan, J., Dreams, Nightmares, and Disturbed Sleep: Contentment Magazine, Aug 2021

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Jernigan, J., A Quick Guide to Beating Burnout: Wellness Council of America, 2017

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Sleep and Sleep Disorders: CDC, September, 2022

- Pinterest (free domain)

- Issues in Nursing, 15(3), 2010. McCarthy, J., Montverde, S., The Standard Account of moral Distress and Why We Should Keep It: HEC Forum 30(4), 2018

- Hertelendy, A., Gutberg, J., et al, Mitigating Moral Distress in Leaders of Healthcare Organizations: A Scoping Review: Journal of Healthcare Management, American College of Healthcare Executives Journal, 67(5), October 2022

- Pinterest (free domain)