At first glance, it might seem strange that both online classes and degree programs are growing while college enrollment has been declining for more than a decade. But Hill explained to me that lost tuition revenue is driving the online shift. Online classes and programs are a way for colleges to reach students who live far from their area. They also appeal to older working adults who cannot come to campus every day. The quest for new students (and their tuition payments) have become more critical for many colleges as there are fewer college-age students in many regions of the country – a population drop that’s spreading throughout the country and will soon affect colleges nationwide. In higher education, it’s called the “demographic cliff.”

“It’s starting to come down to schools saying, ‘If we’re gonna stay alive as an institution, we’re going to be a lot more aggressive in finding ways to reach students,” said Hill. “It’s an existential issue.”

In recent months, several colleges have announced that they’re transforming into purely online institutions to avoid closure. Goddard College in Vermont said it will end on-campus residency programs beginning in the fall of 2024. It had been faced with declining enrollment and tuition revenue, combined with rising operating costs. Three University of Wisconsin campuses are also ending in-person instruction: UW Milwaukee – Washington County, UW Oshkosh – Fond du Lac, and UW Green Bay – Marinette.

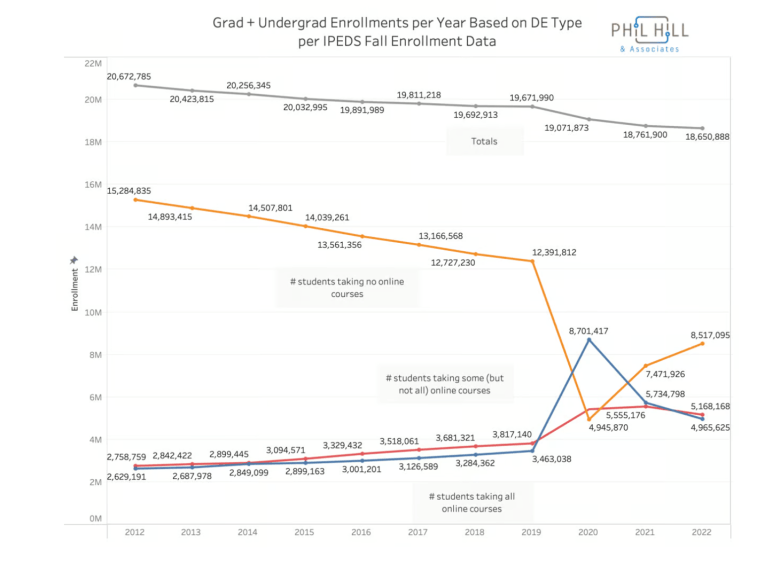

Four-year public colleges and universities are behind the large post-pandemic increases in online learning, according to Hill. In the past, for-profit colleges, primarily online nonprofits and community colleges had been large drivers of the online trend.

The pandemic expedited the shift, Hill said, because many colleges hemorrhaged students during the public health crisis and got an early taste of the demographic cliff ahead. Colleges are restructuring for the future. At the same time, nearly all faculty tried teaching online in 2020 and that experience chipped away at their previous resistance, said Hill. Professors may still not be fans of online learning, but they’re not protesting it as much.

Another phenomenon is that colleges are banding together to offer online classes that individual campuses, especially ones in rural areas, cannot afford to teach on their own. It’s a bit like airline code sharing. Hill said the Colorado Community College System, one of his clients, is developing online courses that all 13 colleges can share with their students.

For students, the online shift is a mixed bag. In some cases, it means they can still take classes that otherwise might not be offered, or they can finish their degrees at an institution that might otherwise have shut down. But there’s a large body of research showing that students don’t learn as much from an online course and are more likely to fail or drop out.

One change from pre-pandemic times, according to Hill, is that more online instruction is now scheduled. Lectures still tend to be recorded for viewing at one’s convenience, but students are often required to log in for a discussion or an activity over Zoom. In entirely “asynchronous” courses, students can log in whenever they want. Often that means that they don’t log in at all.

Keeping students motivated online remains a challenge for community colleges, Hill said. “If you’re going to teach online, you still need comprehensive student support, but community colleges are resource constrained,” he said, explaining that they don’t have enough advisers and counselors to make sure students are logging in and keeping up with their work. Often, financial, work and family responsibilities interfere with school.

It’s worth noting that far fewer students are learning online at the most selective colleges. Fewer than 20% of students are taking an online course at Harvard, Yale, Swarthmore, Williams and a handful of other elite colleges, according to Hill’s analysis. It’s yet another example of how schooling is changing between the haves and the have-nots.