New York put resources and effort into creating high-quality programs for all. It initially invested $300 million in 2014, spending the same amount on rich and poor alike, $10,000 per child. That spending increased over the years. Currently the city pays preschool providers between $18,000 to $20,000 per student, according to Gregory Brender, director of public policy at the Day Care Council of New York, Inc. That’s comparable to some private programs in the city. The city also hired 120 people to observe classrooms to monitor quality and share the ratings with parents to help them pick the best programs for their children.

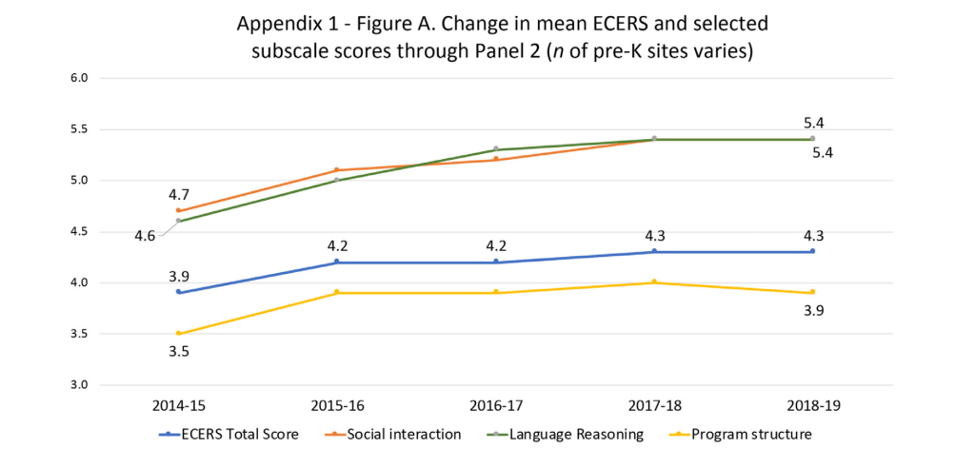

Fuller analyzed these ratings and characterized the overall quality of New York City’s 1,800 preschools as “medium to slightly above medium quality” from 2015 to 2019. They’re not as good as San Francisco’s, but much better than Florida’s or Tennessee’s preschools, based on qualitative measurements that are commonly used by researchers.

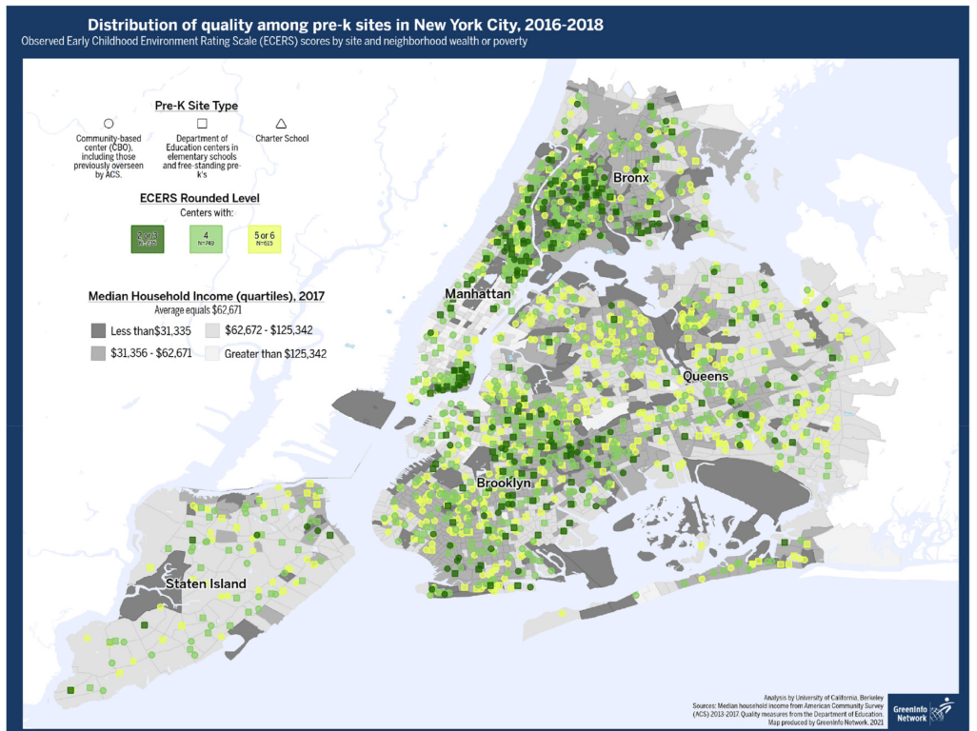

Fuller mapped these observer ratings against census tracts in New York City and noticed that the early childhood programs in poorer neighborhoods, such as East Tremont in the Bronx, were lower rated than public programs offered in wealthier neighborhoods, such as Brooklyn Heights.

Fuller’s team also saw high levels of segregation and many programs that were predominantly filled with Black or Hispanic children. A third of New York City’s preschoolers attend a program that is at least three-quarters populated by one racial or ethnic group. Preschools located in neighborhoods with a high percentage of Black residents were some of the lowest rated, raising concerns that these programs aren’t giving Black children a firm foundation for their future school years.

“It’s a fragile floor especially for kids in predominantly Black communities,” said Fuller. Many of the ratings and observational scores “are falling to very dangerously low levels for those youngsters. And we don’t really know why.”

The quality measures cover a wide range of things, from play space and furniture to the school’s daily routines for going to the toilet and hanging up a coat. Fuller was especially focused on instructional measures, activities and how teachers interact with children.

“Child-teacher relationships are quite different between medium and high-quality pre-K,” said Fuller. “There’s a big difference between teachers that are really down on the floor, engaging with kids versus teachers that are kind of hovering above and not really interacting with youngsters.”

Some aspects of preschool quality, such as physical space, aren’t as important for kids’ future development, Fuller said. But “instructional support,” he said, is highly predictive of kids’ future learning trajectories. One of the biggest gaps between rich and poor, Fuller noticed, was in “program structure.” Low-quality programs weren’t organizing a variety of activities for kids, from playing music and reciting lyrics to playing with math concepts and objects around a table. Kids in low-quality programs also seemed less engaged. Fuller found that programs run by community groups had higher quality overall, regardless of the neighborhood, but city schools provided stronger instructional activities.

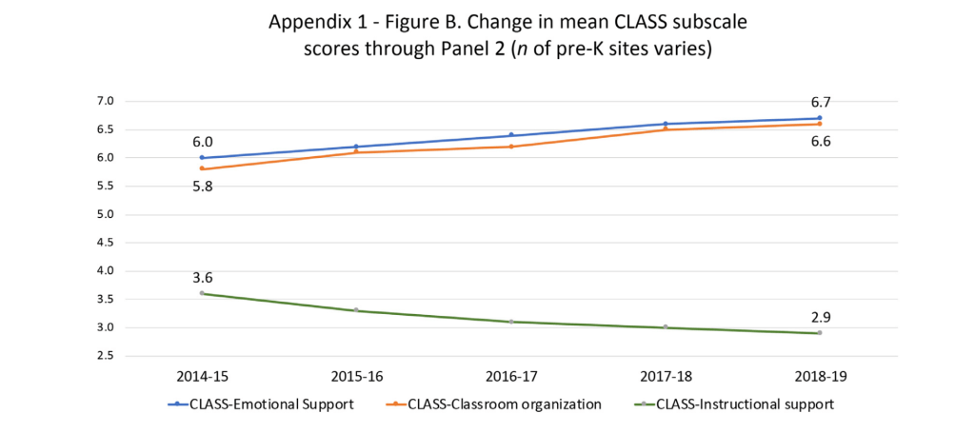

Fuller wants to understand if teacher quality is responsible for the quality differences but he doesn’t yet have data on the training and years of experience of teachers at different preschool sites. New York City has spent a lot on professional development training to improve the instruction in low-quality programs, but other than some big improvements in the first couple years after universal pre-K launched in 2014, Fuller didn’t detect meaningful improvements after 2016. Some aspects of quality, such as instructional support, continued to deteriorate throughout the city’s preschools.

Before New York City introduced universal pre-K, low-income children already had access to free preschool through community organizations financed by federal Head Start and the Child Care and Development Block Grant. But participation was low. After a big marketing campaign to encourage everyone to go to free preschool, the number of poor children in preschool more than tripled from about 12,500 in 2013 to more than 37,000 in 2015. But more than 12,000 poor children remained not enrolled, according to a 2015 estimate by Berkeley researchers.

The critical question is whether low-income children are better off now, even if their preschool programs are not as good as those of wealthier kids. We’re still waiting for the research to learn whether this pricey preschool experiment is making a difference.