The success of an internal platform is defined by how many teams adopt it. This means that a

platform team’s success hangs on their ability to collaborate with other teams, and specifically to get

code changes into those teams’ codebases.

In this article we’ll look at the different

collaboration phases that platform teams tend to operate in when working with other teams, and

explore what teams should do to ensure success in each of these phases.

Specifically, the three platform collaboration phases we’ll be looking at are

platform migration, platform consumption, and platform

evolution. I’ll describe what’s different in each of these phases,

discuss some operating models that platform teams and product delivery teams

(the platform’s customers)

can adopt when working together in each phase, and look at what cross-team collaboration patterns work

best in each phase.

When considering how software teams collaborate, my go-to resource is the wonderful

Team Topologies book. In chapter 7 the authors

define three Team Interaction Modes: collaboration, X-as-a-service, and facilitating.

There is, unsurprisingly, some overlap between the models I will present in this article

and those three Team Topology modes, and I’ll point those out along the way. I’ll also

refer back to some of the general wisdom from Team Topologies in the conclusion to this

article – it really is an extremely valuable resource when thinking about how teams work

together.

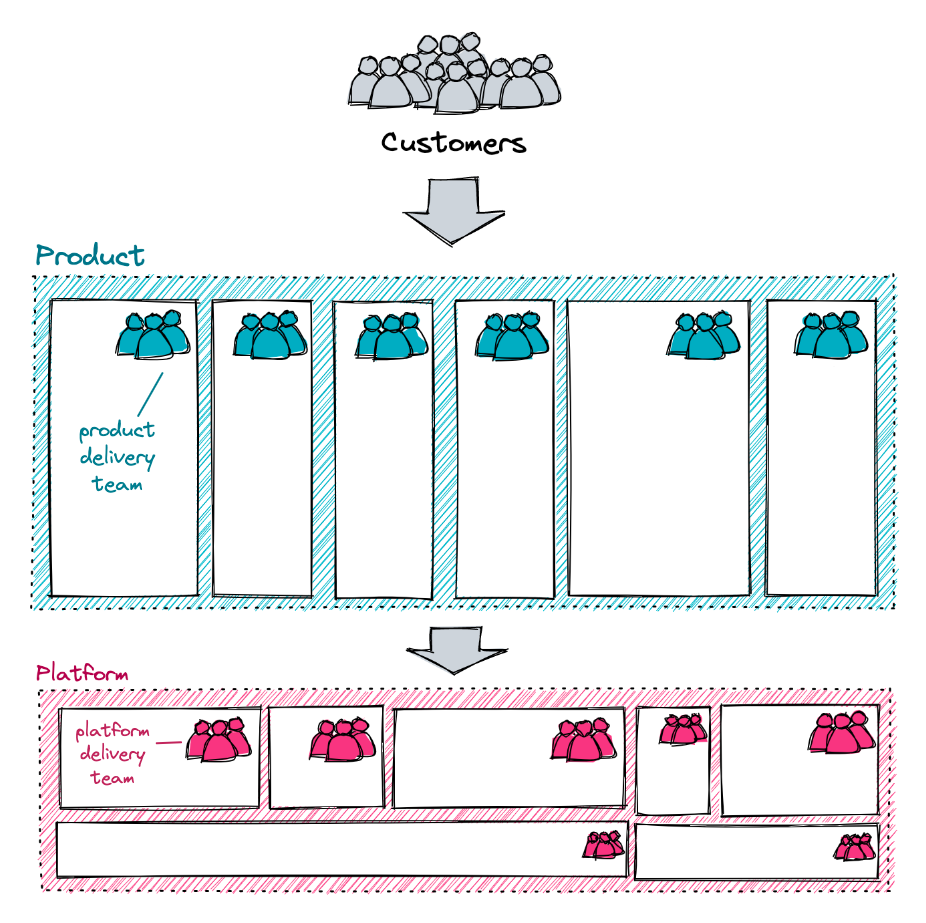

Platform Delivery teams vs. Product Delivery teams

Before we dive in, let’s get clear on what distinguishes a platform team

from other types of engineering team. In this discussion I will often refer to

product delivery teams and platform delivery teams.

A product delivery team builds features for a company’s customers – the

end users of the product they’re building are the company’s customers.

I’ve also seen these types of engineering team referred to as a “feature

team”, a “product team” or a “vertical team”. In this article I’ll use

“product team” as a shorthand for product delivery team.

In contrast, a platform delivery team builds products for other teams inside the

company – the end users of the platform team’s product are other teams

within the company. I’ll be using “platform team” as a short-hand for “platform delivery team”.

In the language of Team Topologies, a product delivery team would typically be characterized

as a Stream Aligned team. While the Team Topologies authors originally defined

Platform Team as a distinct topology, they’ve subsequently come to see “platform”

as a broader concept, rather than a distinct way of working – something I very much agree with. In

my experience when it comes to Team Topologies terminology a good platform tends to operate as either

a Stream Aligned team – with their platform being their value stream – or as an Enabling team, helping

other teams to succeed with their platform. In fact, in many of the cross-team collaboration patterns we’ll

be looking at in this article the platform team is acting in that Enabling mode.

“Platform” > Internal Developer Platform

There’s a lot of buzz at the moment around Platform Engineering, primarily

focused on Internal Developer Platforms (IDPs). I want to make it clear that

the discussion of “platforms” here is significantly broader; it encompasses other internal products

such as a data platform, a front-end design system, or an experimentation platform.

In fact, while we will be primarily concerned with technical platforms, a lot of the ideas

presented here also apply to internal products that provide shared business capabilities – a money movement

service at a fintech company, or a product catalog service at an e-comm

company. The unifying characteristic is that platforms are internal products used by other teams within an organization.

Thus, platform teams are building products whose customers are other teams within their company.

platform teams are building products whose customers are other teams within their company

Phases of platform adoption

Ok, back to the different types of cross-team work. We’re going to look

at three scenarios that require collaboration between platform teams

and product delivery teams: platform migrations, platform consumption, and

platform evolution.

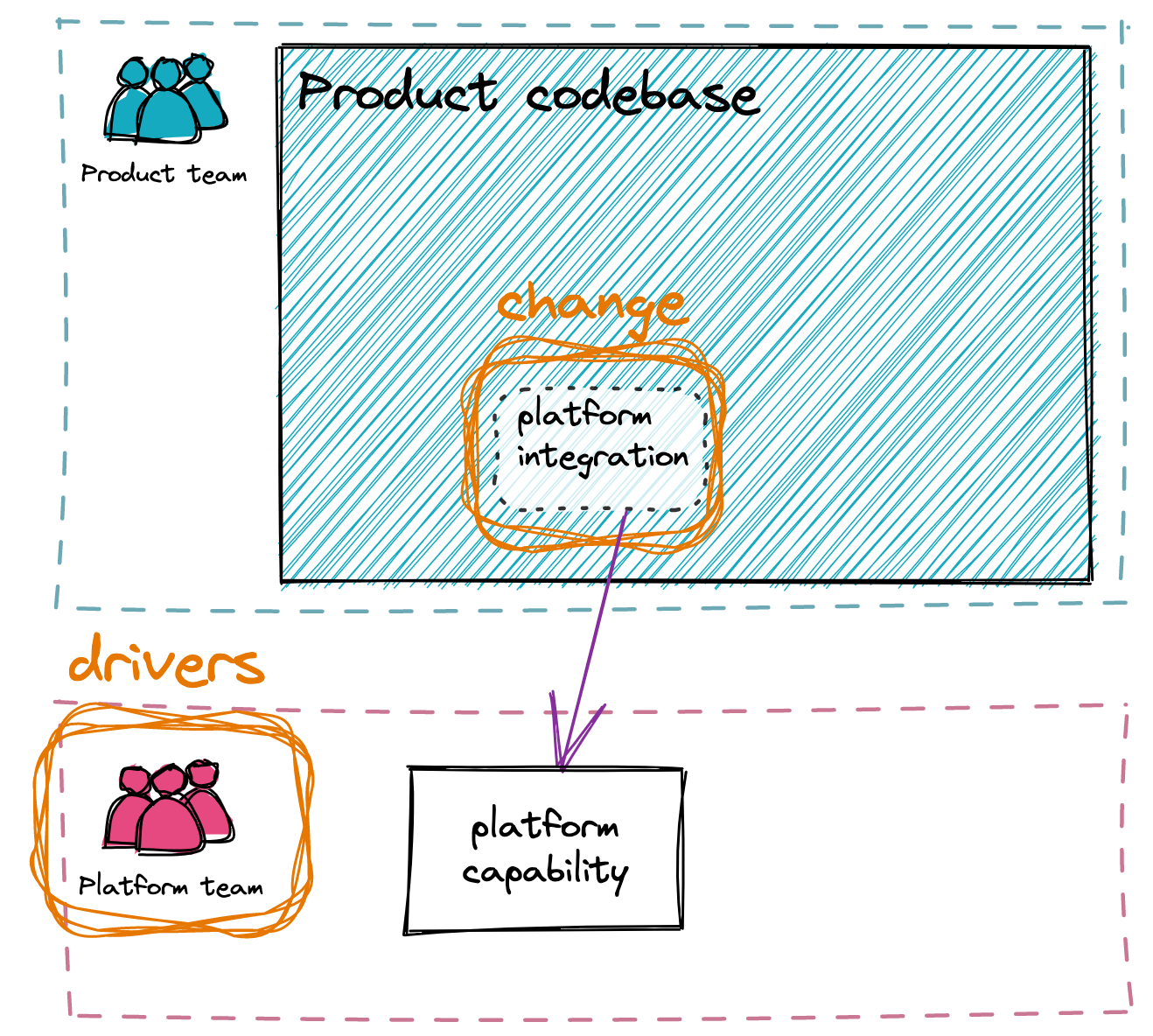

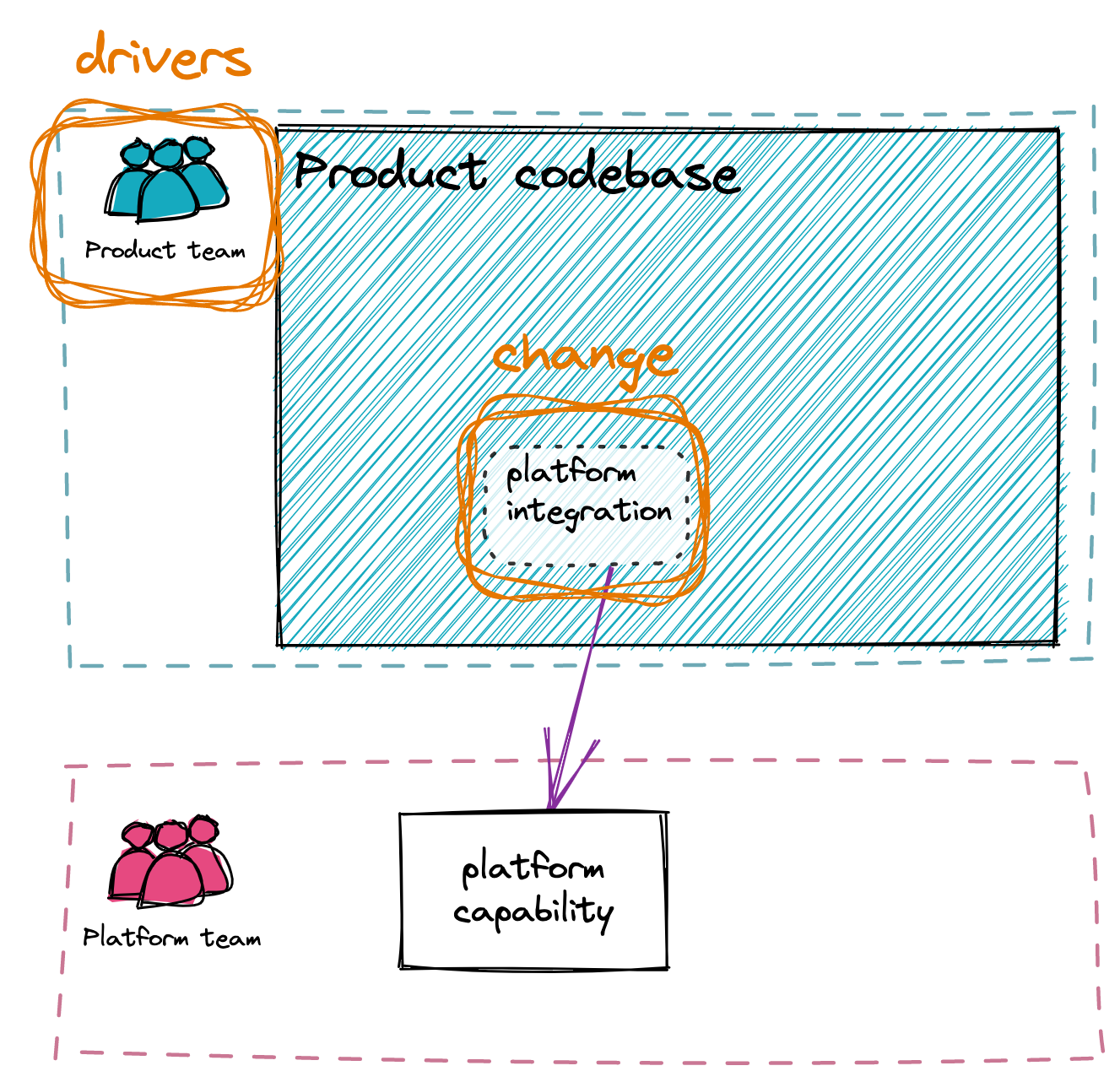

As we look at these three phases, it’s important to note two specific

characteristics: which team is driving the work, and which team owns

the codebase where the work will happen. The answers to those two

questions greatly affect which collaboration patterns make sense in each

scenario.

Platform Migrations

We’ll start by looking at platform migrations. Migrations involve

changes to product teams’ codebases in order to switch over to some new

platform capability.

We see that in these situations it’s a platform team that’s driving the

changes, but the ownership of the codebase that needs changing is sits with a different team – a product team.

Hence the need for cross-team collaboration.

Examples of migration work

What types of changes are we talking about? One relatively simple

migration would be a version upgrade- upgrading a shared component

library, or upgrading a service’s underlying language runtime.

A common, larger migration would be replacing direct integration of

a 3rd party system with some internal wrapper – for example, moving

logging, analytics, or observability instrumentation over to using a

shared internal library maintained by a platform team, or replacing

direct integration with a payment processor with integration via an

internal gateway service of some kind.

Another type of migration might be replacing an existing integration into a deprecated

internal service with an integration into it’s replacement – perhaps moving from an old User

service to a new Account Profile service, or migrating usage of a

credit-puller and credit-reporting service to a new consolidated

credit-agency-gateway service.

A final example would be an infrastructure-level re-platforming –

dockerizing a service owned by a product team, introducing a service

mesh, switching a service’s database from MySQL to Postgres, that sort

of thing.

Note that with platform migrations the product team is often not especially motivated

to make these changes. Sometimes they are, if the new platform is going to provide some

particularly exciting new capabilities, but often they are being asked to make this shift

as part of a broader architectural initiative without actually getting a huge amount of value

themselves.

Collaboration Patterns

Let’s look at what cross-team

collaboration patterns would work for platform migration

work.

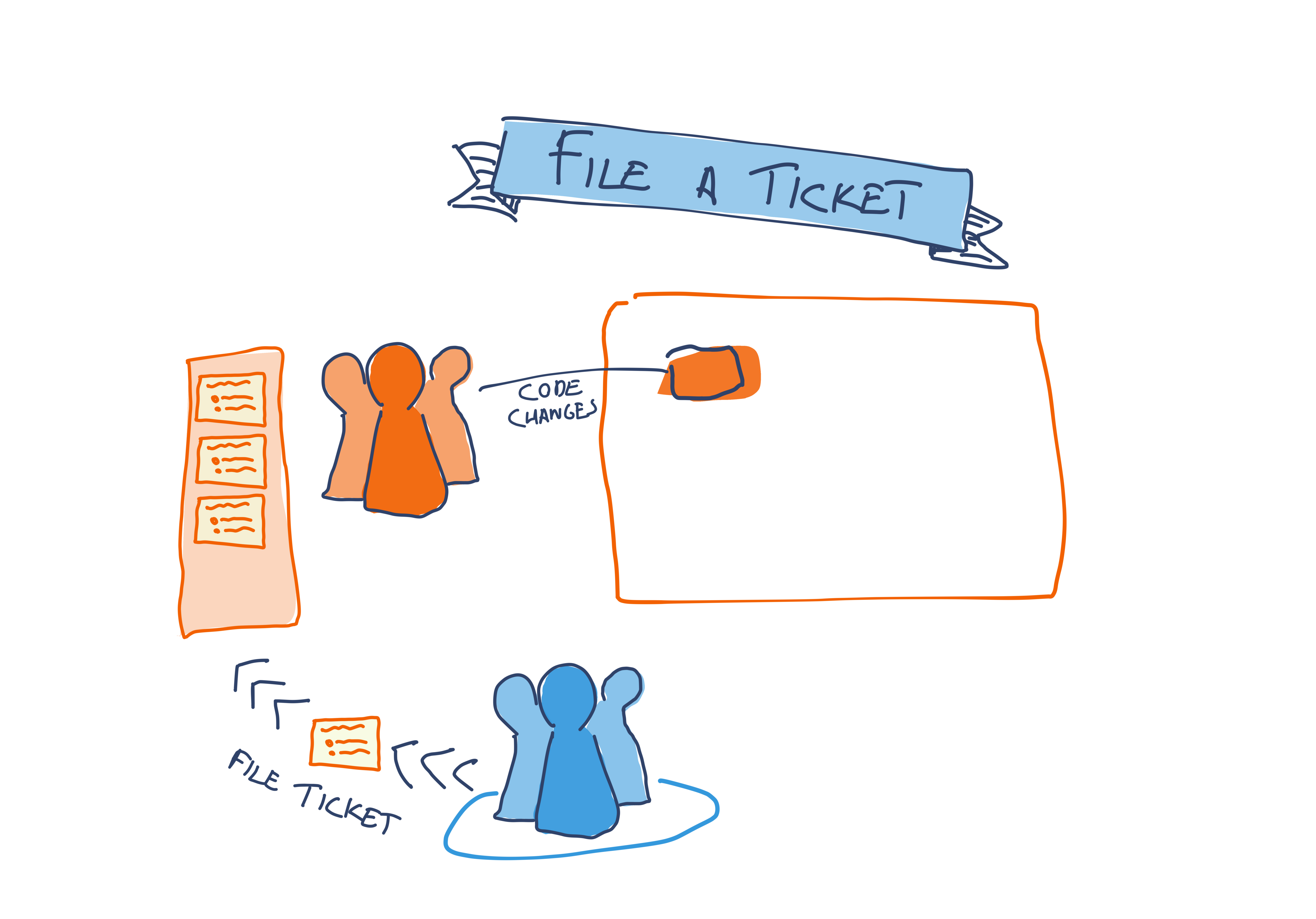

Farm out the work

The platform team could File a Ticket in the

product teams’ backlogs, asking them

to make the required changes themselves.

This approach has some advantages. It’s scalable – the

implementation work can be farmed out to all the product teams whose

codebases need work. It’s also trackable and easy to manage – often

the ticket filing can be done by a program manager or other project

management type.

However, there are also some drawbacks. It’s really slow –

there will be long lead times before some product teams get around

to even starting the work. Also, it requires prioritization

arm-wrestling – the teams being asked to do this work often don’t

receive tangible benefits, so it’s natural that

they’re included to de-prioritize this work over other tasks that

are more urgent or impactful.

Platform team does the work

The platform team might opt to make changes to the product team’s

codebases themselves, using three similar but distinct patterns –

Tour of Duty, Trusted Outsider, or Internal Open Source.

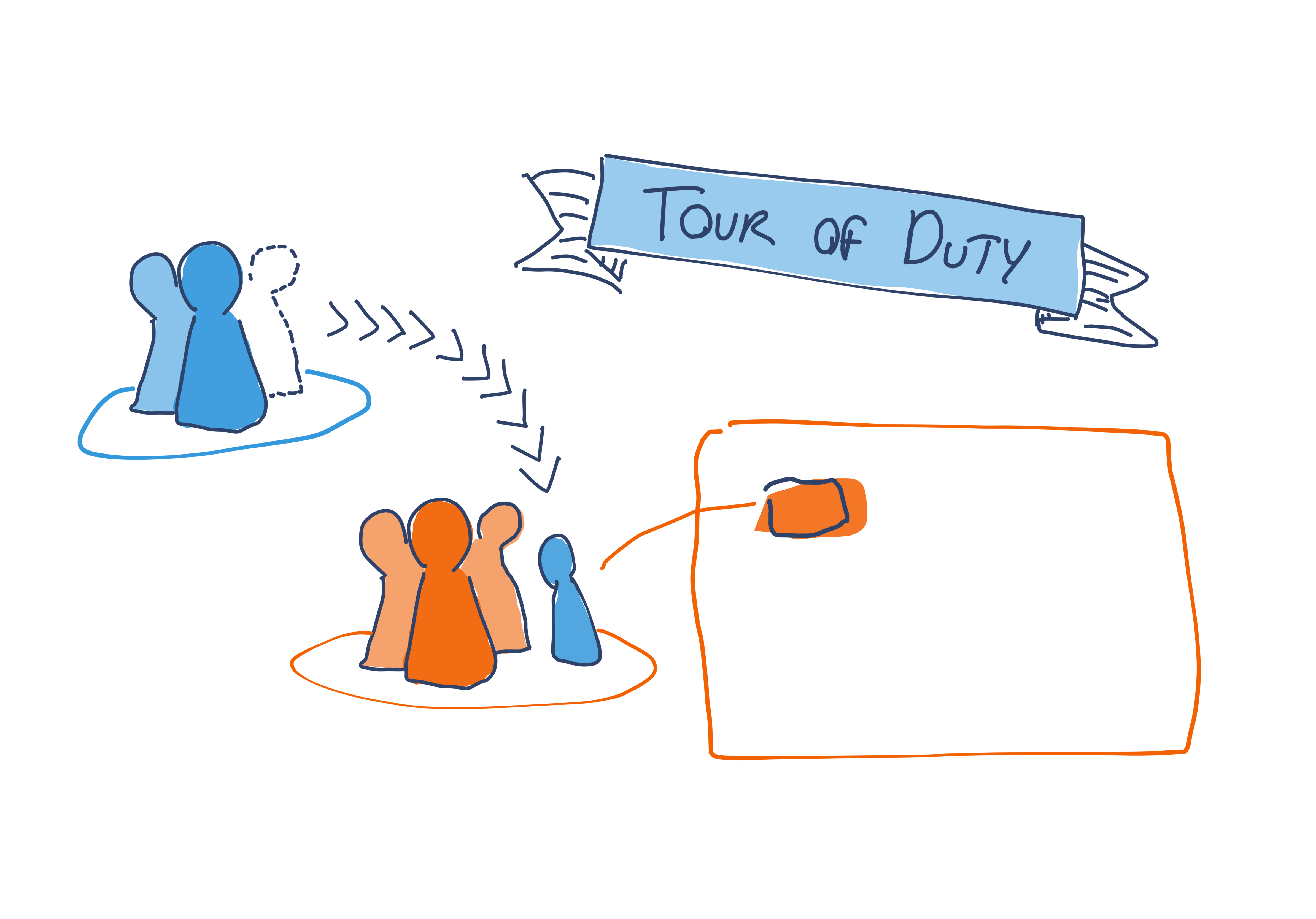

With Tour of Duty, an engineer from the

platform team would “embed” with the product team and do the work

from there.

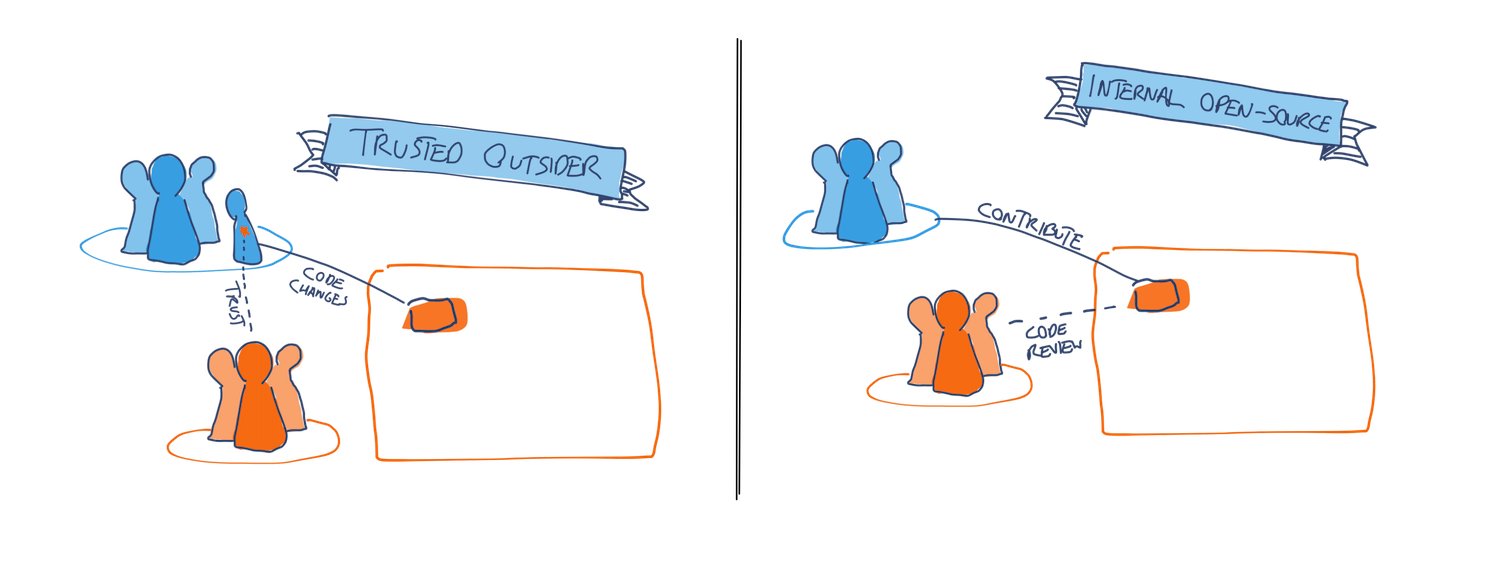

With Trusted Outsider and Internal Open Source the product team would accept pull

requests to their codebase from an engineer in the platform team.

The distinction between these last two patterns lies in whether

any engineer can make contributions to the product

team’s codebase, or only a small set of trusted external

contributors. It’s rare to see product delivery teams make the

investment required to support the full internal open-source

approach, but not unusual for contributions to be accepted by a

handful of trusted platform engineers.

Just as with taking the file-a-ticket path, having the platform

team do the work comes with some pros and cons.

On the plus side, this approach often reduces the lead time to

get changes made, because the team that needs the work to be done

(the platform team) is also the one doing the work. Aligned

incentives mean that the platform team is much more likely to

prioritize their work than the product team which owns the codebase

would.

On the negative side, having the platform team do the migration

work themselves only works if the product team can support

it. They either need to be comfortable with a platform engineer

joining their team for a while, or they need to have already spent

enough time with a platform engineer that they trust them to make

changes to their codebase independently, or they need to have made

the significant investment required to support an internal

open-source approach.

Another negative is that this do-it-yourself strategy is not

scalable. There will always be less engineering capacity on the

platform team compared to the product delivery teams, and not

delegating engineering work out to the product teams leaves all that

capacity on the table.

Really, it’s a bit more complicated

In reality, what often happens is a combination of these

approaches. A platform team tasked with a migration might have

a program manager file tickets with 15 product delivery teams and then

spend some period of time cajoling them to do the work.

After a while, some teams will

have done the work themselves but there will be stragglers who are

particularly busy with other things, or just particularly

disinclined to take on the migration work. The platform team will

then roll up their sleeves and use some of the other, less scalable

approaches and make the changes themselves.

Platform Consumption

Now let’s talk about another phase of platform adoption that involves

cross-team collaboration: platform consumption. This is the

“steady state” for platform integration, when a product delivery team

is using platform capabilities as part of their day-to-day feature

work.

One example of platform consumption would be a product team

spinning up a new service using a service chassis

that’s maintained by an infrastructure platform team. Or a

product team might be starting to use an internal customer analytics

platform, or starting to store PII using a dedicated Sensitive Data

Store service. As an example from the other end of the software stack,

a product team starting to use components from a shared UI component

library is a type of platform consumption work.

The key difference between platform consumption work vs platform

migration work is that the product team is both the driver of the work, and

the owner of the codebase that needs changing – the product team has a broader goal of its

own, and they are leveraging the platform’s features to get there. This is in contrast

to platform migration where the platform team is trying to drive changes into other team’s codebase.

With platform consumption With the product team as both driver and owner, you might think that this platform

consumption scenario should not require cross-team collaboration.

However, as we will see, the product team can still need some support

from the platform team.

Collaboration patterns

A worthy goal for many platform teams is to build a fully self-service

platform – something like Stripe or Auth0 that’s so well-documented and

easy to use that product engineers can use the platform without needing

any direct support or collaboration with the platform team.

In reality, most internal platforms aren’t quite there,

especially early on. Product engineers getting started with an

internal platform will often run into poor documentation, obtuse

error messages, and confusing bugs. Often these product teams will

throw up their hands and ask the platform team to pitch in to help

them get started using the features of an internal platform.

When a platform consumer is asking the platform owner for

hands-on support we are back to cross-team collaboration, and once

again different patterns come into play.

Professional services

Sometimes a product team might ask the platform team to

write the platform consumption code for them. This might be because

the product team is struggling to figure out how to use the

platform. Or it could be because this approach would require less

effort from the product team. Sometimes it’s just a misunderstanding

where the product team doesn’t think they’re supposed to do the work

themselves – this can happen when shifting into a devops model where

product teams are self-servicing their infra needs, for example.

In this scenario the platform team sort of becomes a little

professional services group within the engineering org, integrating

their product into their customer’s systems on their behalf.

This professional services model uses a combination of

collaboration patterns. Firstly, a product team will typically File a Ticket

requesting the platform team’s services. This is the same

pattern we looked at earlier for Platform Migration work, but

inverted – in this situation it’s the product team filing a ticket

w. the platform team, asking for their help. The platform team can

then actually perform the work using either the Trusted Outsider or

Internal Open Source patterns.

A common example of this collaboration model is when a product

team needs some infrastructure changes. They want to spin up a new

service, register a new external endpoint with an API gateway, or

update some configuration values, so they file a ticket with a

platform team asking them to make the appropriate changes.

This pattern is commonly seen in the infra space, because it

perpetuates an existing habit – before self-service infra, filing

a ticket would have been the standard mechanism for a product team

to get an infrastructure change made.

White-glove onboarding

For a platform that’s in its early stages and lacking in good

documentation, a platform team might opt to onboarding new product

teams using a “white glove” approach, working side-by-side with

these early adopters to get them started. This can help kickstart

the adoption of a new platform by making it less onerous for the product

teams who go first. It can also give a platform team really valuable

insights into how their first customers actually use the platform’s

features.

This white-glove model is typically achieved using the Tour of Duty

collaboration pattern – one or more platform engineers will

spend some time embedded into the consuming team, doing the

required platform integration work from within that team.

Hands-on doesn’t scale

We can see that the level of hands-on support that a platform

team needs to provide to consumers can vary a lot depending

on how mature a platform’s Developer Experience is – how well it’s

documented, how easy it is to integrate and operate against.

In the early days of a platform, it makes sense for platform

consumption to require a lot of energy from the platform team

itself. The developer experience is still a little rocky, platform

capabilities are perhaps still being built out, and consuming teams

are perhaps a little skeptical to invest their own time as guinea

pigs. What’s more, working side-by-side with product teams is a

great way for a platform team to understand their customers and what

they need!

However hands-on support doesn’t scale, and if broad platform

adoption is the goal then a platform team must invest in the

developer experience of their platform to avoid drowning in

implementation work.

It’s also important to clearly communicate to platform users what

support model they should expect. A product team that has received

white-glove support in the early days of platform adoption will look

forward to enjoying that experience again in the future unless

informed otherwise!

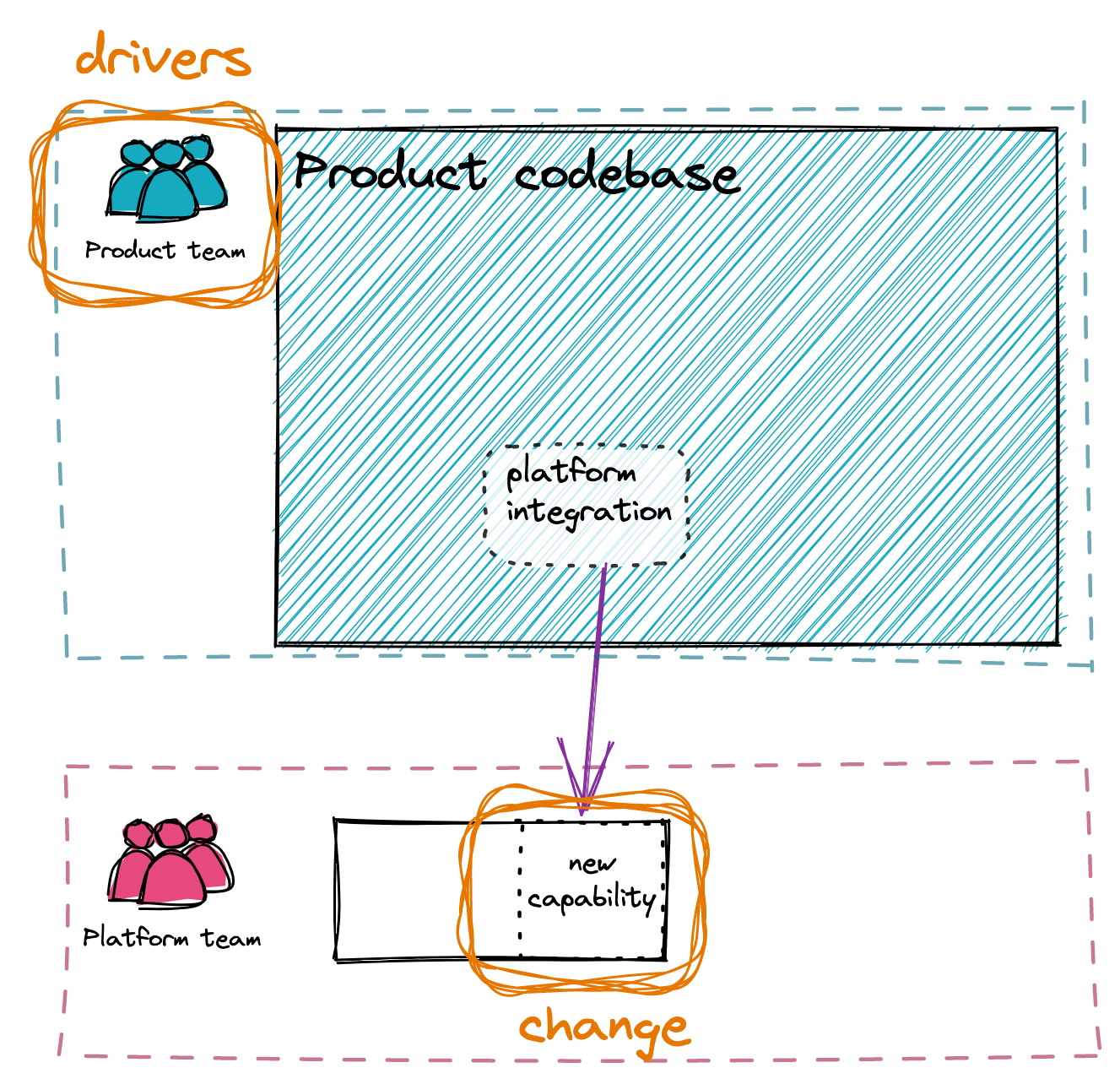

Platform Evolution

Let’s move on to look at our final platform collaboration phase: platform

evolution. This is when a team using a platform needs changes in the platform itself, to fill a gap in the platform’s

capabilities.

For example, a team using a UI component library

might need a new type of <Button> component to be added, or for

the existing <Button> component to be extended with additional

configuration options. Or a team using a service chassis might want that chassis to emit more

detailed observability information, or perhaps support a new

serialization format.

We can see that in Platform Evolution phase the team’s respective

roles are the opposite of Platform Migration – now it’s the product

team that’s driving the work, but the changes need to occur in the

platform team’s codebase.

Let’s look at which cross-team

collaboration patterns make sense in this context.

File a ticket

The product team could File a Ticket with the platform team,

asking them to make the required changes to their platform. This

tends to be a very frustrating approach. Often a product team only

realizes that the platform is missing something at the moment that

they need it, and the turnaround time for getting the platform team

to prioritize and perform the work can be way too long – platform

teams are typically overloaded with inbound requests. This leads to

the platform team becoming a bottleneck and blocking the product

delivery team’s progress.

Move engineers to the work

With sufficient warning, teams can plan to fill a gap in

platform capabilities by temporarily re-assigning engineers to work

on the required platform enhancements. Product engineers could do a

Tour of Duty

on the platform team, or alternatively a platform engineer could

join the product team for a while as an Embedded Expert.

Moving engineers between teams will inevitably lead to a

short-term impact on productivity, but having an embedded engineer

can increase efficiency in the long run by reducing the amount of

cross-team communication that’s needed between the product and the

platform teams. The embedded engineer acts as an ambassador,

smoothing the communication pathways and reducing the games of

telephone.

This equation of fixed upfront costs and ongoing benefits means

that re-assigning engineers is an option best reserved for larger

platform improvements – moving an engineer to another team for a

couple of weeks would be more disruptive than helpful.

These types of temporary assignments also require a relatively

mature management structure to avoid embedded engineers feeling

isolated. With an Embedded Expert – a platform engineer re-assigned

to a product team – there’s also a risk that they become a general

“extra hand” who’s just doing platform consumption work, rather than

actively working on the improvements to the platform that the

product team need.

Work on the platform from afar

If a platform team has embraced an Internal Open Source approach then a

product team has the option of directly implementing the required platform changes

themselves. The platform team’s role would be mostly consultative,

providing design recommendations and reviewing the product team’s

PRs. After a few PRs, a product engineer might even gain enough

trust from the platform team to be granted the commit bit and become

a Trusted Outsider.

Many platform teams aspire to get to this situation – wouldn’t it

be great if your customers were empowered to implement their own

improvements, and save you from having to do the work! However, the

reality of internal open-source is similar to open-source in general

– it takes a surprising amount of investment to support external

contributions, and the large majority of consumers don’t become

meaningful contributors.

Platform teams should be careful to not open up their codebase to

external contributions without making some thoughtful investments to

support those contributions. There can be deep frustration all

around if a platform team proudly proclaim in an all-hands that

their codebase is a shared resource, but then find themselves

repeatedly telling contributors from other teams “no, no, not like

THAT!”.

Conclusion

Having considered Platform Migration, Consumption, and Evolution, it’s clear that there’s a rich variety in how

teams collaborate around a platform.

It’s also apparent that there isn’t one correct form of collaboration. The best way to work together depends not just on

what phase of platform adoption a team is in, but also on the maturity of the interfaces between teams and between systems.

Expecting to be able to integrate a new internal platform in the same hands-off, as-a-service mode that you’d use with a

mature external service is a recipe for disaster. Likewise, expecting to be able to easily make changes to a product delivery

team’s codebase when they’ve never accepted external contributions before is not a reasonable assumption to make.

be collaborative, but only for a bit

In Team Topologies, they point out that the best way to design good boundaries between two teams is to initially work together

in a focused, very collaborative mode – think of patterns like Embedded Expert and

Tour of Duty. This period can be used to explore where the best boundaries

and interfaces to create between systems, and between teams (Conway’s Law tells us that these two are inextricably entwined).

However, the authors of Team Topologies also warn that it’s important to not stay in this collaborative mode for too long. A platform

team should be working hard to define their interfaces, looking to move quickly to an “as-a-service” mode, using patterns like

File a Ticket and Internal Open Source. As we discussed in the Platform Consumption section,

the more collaborative interaction models simply won’t scale as far as the platform team is concerned. Additionally, collaborative modes

impose a much greater cognitive load on the consuming teams – moving to more hands-off interaction styles allows product delivery teams

to spend more of their time focused on their own outcomes. In fact, Team Topologies considers this reduction of cognitive load as

the defining purpose of a platform team – a framing which I very much agree with.

Navigating this shift from highly collaborative to as-a-service is, in my opinion, one of the biggest

challenges that a young platform team faces. Your customers become comfortable with the high-touch experience. Building great documentation is hard.

Saying no is hard.

Platform teams operating in a collaborative mode should be keeping a weather eye for scaling challenges. As the need for a shift

towards a more scalable, hands-off approach appears on the horizon the platform team should begin signaling this shift to their customers.

An early warning as to how the interaction model will change – and why – gives product teams a chance to prepare and to start

shifting their mental model of the platform towards something that’s more self-sufficient.

The transition can be painful, but vacillating makes it worse. A product delivery team will appreciate clearly

communicated rules of engagement around how their platform providers will support them. Additionally, removing the crutch of hands-on

collaboration provides a strong motivation to improve self-service interfaces, documentation, and so on. Conway’s Law is in effect here –

redefining how teams integrate will put pressure on how the team’s systems integrate.

A platform team succeeds on the back of collaboration with other teams, and that collaboration can take many forms. Choosing the right

form involves considering the type of platform work the other team is doing, and being realistic about the current state of both teams

and their systems. Getting this right will allow the platform team to grow adoption of their platform, but as that adoption grows the

team must also be intentional in moving to collaboration modes that are less hands-on, more scalable, and minimize cognitive load for the

consumers of that platform.