The sharp growth in dual enrollment has raised a lot of questions about course content and whether students are really producing college-level work. John Fink, an expert in dual enrollment at the Community College Research Center, acknowledged that quality is uneven. That’s not surprising when 80% of high schools are now offering these courses and there’s decentralized oversight among thousands of colleges around the country. But colleges that oversee these courses are trying to improve quality, Fink said. (The Community College Research Center is a unit of Teachers College, Columbia University. The Hechinger Report is also an independent news organization based at Teachers College, but the two entities are not affiliated.)

Despite concerns about course rigor, research points to better outcomes for students. Between similar students with comparable grades and family backgrounds, the student who takes a dual enrollment class is more likely to graduate high school, enroll in college and earn a college degree, many studies have found. In 2017, the What Works Clearinghouse, a unit of the Department of Education that reviews education research, gave dual enrollment its stamp of approval with a strong level of evidence for it.

In qualitative research interviews, students described how dual enrollment courses taught them how to take notes or study for a test, helping them feel more prepared for college. Much of the benefit may be in boosting a student’s confidence and soft skills, and not necessarily in teaching academic content, University of Iowa’s An explained.

A big downside to dual enrollment is that students of color are underrepresented. That’s an ironic outcome given that advocates, including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, pushed the expansion of these programs to help promote college going and attainment among Black and Hispanic students. Only one fifth of high schools have managed to enroll Black and Hispanic students in dual enrollment classes at the same or higher rates as white students, Fink said. (The Gates Foundation is among the many funders of The Hechinger Report.)

Another reason for the rapid expansion of dual enrollment may be financial. Dual enrollment courses are money losers for many community colleges, according to Fink at the Community College Research Center. That’s because colleges receive a discounted per-pupil allotment for each high schooler who signs up. Each state funds dual enrollment differently, often through a combination of state and school district budgets. Sometimes families need to contribute too, but it tends to be a lot cheaper than a usual college course.

But colleges can turn dual enrollment programs into a modest money maker when they serve more students, according to a February 2023 analysis by the Community College Research Center. Once fixed costs are covered, each additional student means an increase in revenues. For example, adding an additional high school teacher to an existing instructor training program isn’t very costly and could open up dozens more student slots, each generating income that flows to the college.

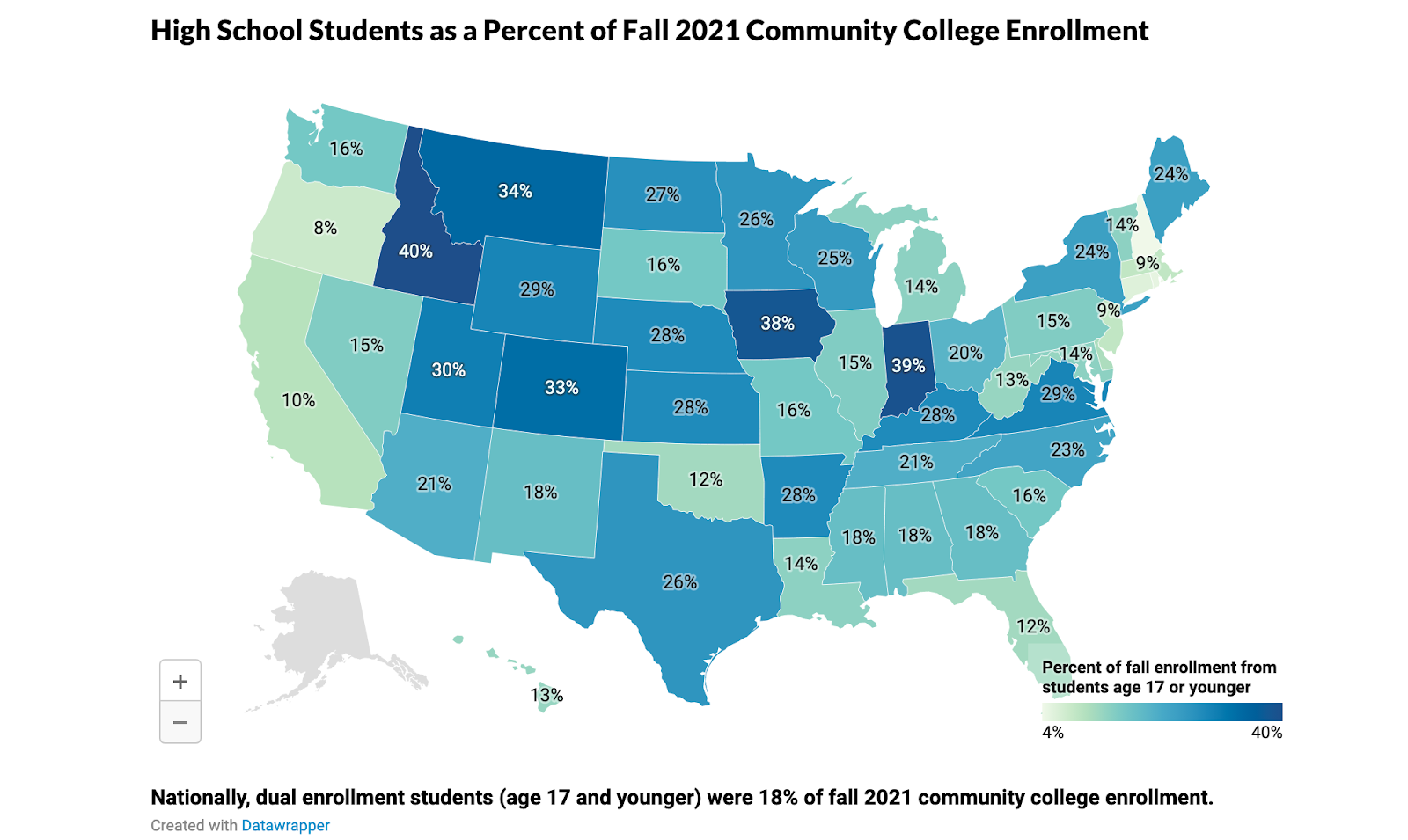

The reason that dual enrollments have become such a big slice of community colleges’ offerings is not only because more high school students are taking these courses, but also because fewer traditional students want to attend community colleges. When the pandemic hit in 2020, there were shocking double digit drops in enrollment at community colleges. Dual enrollment classes at many high schools temporarily shut down too, but they dramatically rebounded in 2022-23. Meanwhile, traditional students haven’t been returning to community colleges in large numbers, thanks to a strong job market. High school students even make up the majority of students at 31 community colleges, my colleague Jon Marcus found.

Precise numbers on exactly how many high schoolers are taking dual enrollment classes are hard to come by. The best data is from the National Student Clearinghouse, which receives enrollment data from most colleges in the country. But colleges report only the ages of their students and not whether they have finished high school. The estimates for dual enrollees are based on students 17 years and under and cross-checked against high school records available to the National Student Clearinghouse. We should get a clearer picture next year when the Department of Education is expected to release a more accurate report on the numbers, broken down by race and ethnicity.

This story about dual enrollment classes was written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Proof Points and other Hechinger newsletters.