The key to any successful startup is close collaboration between product

and engineering. This sounds easy, but can be incredibly difficult. Both

groups may have conflicting goals and different definitions of success that

have to be reconciled. Engineering might want to build a product that is

perfectly scalable for the future with the best developer experience.

Product might want to quickly validate their ideas, and put features out

that will entice customers to pay for the product. Another example that’s

common to see is an engineering-led “engineering roadmap” and a product-led

“product roadmap” and for the two to be completely independent of each

other, leading to confusion for product engineering. These two mindsets

put two parts of your organization at odds. The easy path is to skip the

difficult conversations and operate within silos, coming together

infrequently to deliver a release. We believe that aligning these two

disparate organizations into cohesive team units removes organizational

friction and improves time to value.

How did you get into the bottleneck?

At the beginning of a startup’s journey, aligning is natural because

you are a small team working closely together, and likely the product and

tech leaders had close personal relationships before the company was

founded. The initial startup idea is very strong and as it quickly gains

traction, what to work on next is obvious to all groups. As the company

grows, however, skill-based verticals begin to appear with more layers of

management, and these managers don’t always put the effort in to create

an effective working relationship with their peers. Instead, they focus on

urgent tasks, like keeping the application running or preparing for a

funding round. At the same time, the startup faces a critical juncture where the company needs to

to decide how to best invest in the product, and needs a holistic

strategy for doing so.

Well-run startups are already working in cross-functional product

teams. Some functions will naturally work well together because they fall

under the same vertical hierarchy. An example would be development and

testing — well integrated in startups, but often siloed in traditional

enterprise IT. However, in the scaleups we work with, we find that product

and technical teams are quite separated. This happens when employees align

more with their function in an Activity Oriented

organization rather than with an Outcome Oriented team, and it

happens at every level: Product managers are not aligned with tech leads

and engineering managers; directors not aligned with directors; VPs not

aligned with VPs; CTOs not aligned with CPOs.

Ultimately, the bottleneck will be felt by reduced organizational

performance as it chokes the creation of customer and business value.

Startups will see it manifest in organizational tension, disruptive

exceptions, unchecked technical debt, and velocity loss. Fortunately,

there are some key signs to look for that indicate friction between your

product and engineering organizations. In this article we will describe

these signs, as well as solutions to lower the communication barriers,

build a balanced investment portfolio, maximize return on investment, and

minimize risk over the long term.

Signs you are approaching a scaling bottleneck

Finger pointing across functions

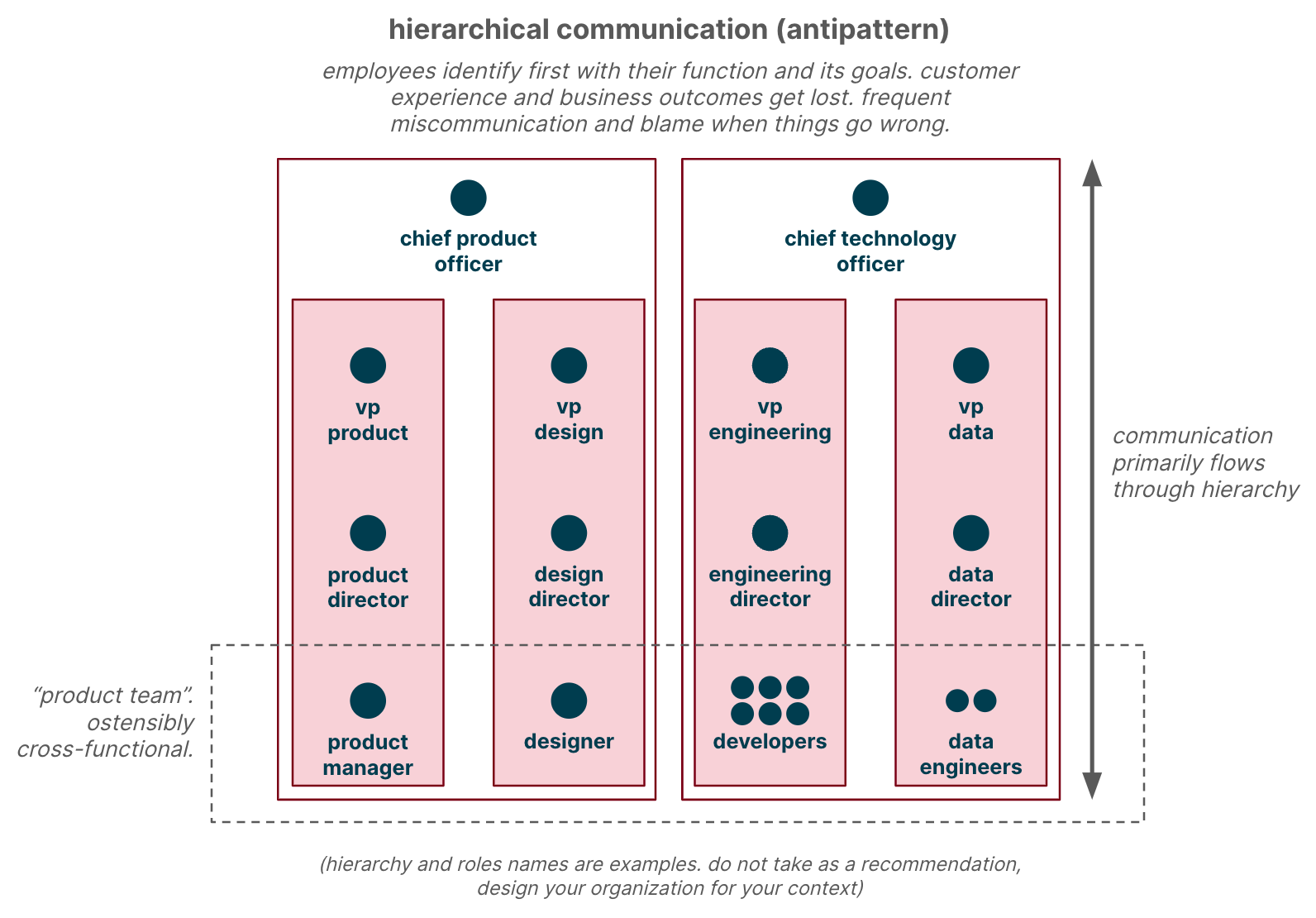

Figure 1: Friction across a typical

hierarchical structure

Team members align themselves with their management structure or

functional leadership as their primary identity, instead of their

business or customer value stream, making it easier for teams to assume

an “us” versus “them” posture.

At its worst the “us vs them” posture can become truly toxic, with little respect for each other. We have seen this manifest when product leaders throw requirements over the wall, and treat the engineering team as a feature factory. They might abruptly cancel projects when the project doesn’t hit its outcomes, without any prior indication the project wasn’t meeting its KPIs. Or conversely, the engineering team continually lets down the product team by missing delivery dates, without warning that this might happen. The end outcome is both sides losing trust in each other.

Engineers often stuck due to lack of product context

When product managers pass off features and requirements without reviewing them with the

engineers (usually within the constructs of a tool like Jira), critical business and customer context can be lost. If

engineers operate without context, then when design or

development decisions need to be made, they must pause and track down the product

manager, rather than make informed decisions themselves. Or worse, they made the decision anyway and

build software based on an incorrect understanding of the product

vision, causing time delays or unused software. This friction disrupts

flow and introduces undue waste in your delivery value stream.

Missed dependencies

When engineers and architects operate with minimal context, the full

scope of a change can be overlooked or misunderstood. Requirements or

user stories lack depth without context. Customer personas can be

ignored, business rules not taken into consideration, technical

integration points or cross-functional requirements missed. This

often leads to last minute additions or unintended disruptions to the

business or customer experience.

Work slipping between the cracks

Tasks slipping between the cracks, team members thinking someone else

will be responsible for an activity, team members nudging each other out

of the way because they think the other team member is operating in

their space, or worse, team members saying “that’s not my job” – these

are all signs of unclear roles and responsibilities, poor communication

and collaboration, and friction.

Technical debt negotiation breakdown

Technical debt is a common byproduct of modern software development

with many root causes that we have

discussed previously. When product and engineering organizations

aren’t communicating or collaborating effectively during product

planning, we tend to see an imbalanced investment mix. This can mean the

product backlog leans more heavily towards new feature development and

not enough attention is directed toward paying down technical debt.

Examples include:

- Higher frequency of incidents and higher production support costs

- Developer burnout through trying to churn out features while working

around friction - An extensive feature list of low quality features that customers quickly

abandon

Teams communicating but not collaborating

Teams that meet regularly to discuss their work are communicating.

Teams that openly seek and provide input while actively working are

collaborating. Having regular status meetings where teams give updates

on different components doesn’t mean a team is collaborative.

Collaboration happens when teams actively try to understand each other

and openly seek and provide input while working.

How do you get out of the bottleneck?

Eliminating the wall between Product and Engineering is essential to

establishing high performing product teams. Cross-functional teams must

communicate and collaborate effectively and they must be able to negotiate

amongst themselves on how best to reach their goals. These are strategies

Thoughtworks has applied to overcome this bottleneck when working with our

scaleup clients.

Identify and reinforce your “First Team”

At its most basic, a product team is a group of individuals who come

together in a joint action around a common goal to create business and

customer value. Each team contributes to that value creation in their own

unique way or with their unique scope. As leaders, it’s important to identify

and reinforce a team dynamic around the creation of value rather than an

organizational reporting structure. This cross-functional product team becomes

a team member’s “first team”. As a leader, when you define your team as your

group of direct reports, you are enabling a tribal concept that contributes to

an “us vs. them” dynamic.

The First Team mindset was defined by

Patrick Lencioni and referenced in many of his works including

The Advantage and The Five Dysfunctions Of A Team: A Leadership

Fable, and while it’s typically used in relation with the

establishment of cross-functional leadership teams as the primary

accountability team rather than organizational reports, the same concept

is applicable here for product teams.

Simply changing your organization’s language, without changing its

behaviors isn’t going to have a measurable impact on your scaling woes. Still,

it’s a simple place to start and it addresses the organizational friction and

larger cultural issues that lie at the root of your performance issues.

Changing the language

The more hands-on an organization is willing to be in breaking

silos, the more likely it is they will be effectively be breaking some

of the implicit ‘versus’ states that have enabled them.

Taking a hands-on approach to moderating the language

used in your organization is a simple first step to breaking down

barriers and reducing friction.

- Referring to your organizational group of practitioners as anything other

than “team” – such as squad, pod, or whatever term fits your organization’s

culture is a small change that can have a strong impact. - Naming your cross-functional product delivery teams,

ideally with the name of their product or value stream, is another simple change that helps

these multi-disciplined individuals adopt a new team identity separate from

their organizational reporting context. - Drop “us” and “them” from the professional vocabulary. Coming up with

alternative terms but keeping the same context of ‘that group over there – which

isn’t this group’ is cheating. We filter ourselves and our language in a

professional environment regularly and this language needs to be added to the

‘not allowed’ list.

Change the behavior

Those of us trying to

change our organizations’ culture need to define the things we want to

do, the ways we want to behave and want each other to behave, to provide

training and then to do what is necessary to reinforce those behaviors.

The culture will change as a result.

Changing an organization’s culture when it isn’t delivering the desired

results is hard. Many books have been written on the subject. By

defining and communicating the expected behaviors of your teams and

their respective team members up front, you set the underlying tone for

the culture you are striving to create.

- Leaders should set a principle and expectation of a blameless culture. When

something goes wrong, it’s a wonderful learning opportunity, to be studied and

used to continuously improve. An example of this is the concept of

a blameless post-mortem. - Set expectations and regularly inspect adoption of desired behaviors. Hold

team members accountable to these behaviors and refuse to tolerate

exceptions. - Orient “team” constructs around value streams instead of functions.

Differentiate “teams” as groups who deliver common value from Communities of

Practices or Centers of Excellence which are typically formed to deepen or

deliver specific competencies such as Product Management or Quality

Assurance. - Acknowledge that some personality types are less compatible than others.

Shift talented people around to find the optimal team synergy.

Define and communicate how your scaleup delivers value

A company is, in many ways, just one large team with one shared goal

— the success of the organization. When product and engineering don’t

have a shared understanding of that goal, it’s hard for them to come to

a collaborative agreement on how to achieve it. To avoid this source of

friction, executives must clearly articulate and disseminate the overall

value their organization provides to its customers, investors, and

society. Leaders are responsible for describing how each product and

service in your portfolio contributes to delivering that value.

Management must ensure that every team member understands how the work

that they do day in and day out creates value to the organization and

its customers.

The goal is to create a shared mental model of how the business

creates value. The best way to do this is highly dependent on the nature

of your business. We have found certain kinds of assets to be both

common and useful across our scaleup clients:

Assets that describe customer and user value

These should describe the value your product and services create, who

they create it for, and the ways you measure that value. Examples

include:

- Business Model Canvas/Lean Canvas

- User Journeys

- Service blueprints

- Personas

- Empathy maps

- Storyboards

- Job forces diagrams

- Product overviews (one-pagers, etc)

Assets that describe your economic model

These should describe the value your company receives from customers,

the cost of creating that value, and the ways in which you measure that

value. Examples include:

- Business flywheels

- Value stream maps

- Wardley maps

- Retention/churn models

- Customer acquisition models

- Customer lifetime value models

- Projected balance sheets and income

statements

Assets that describe your strategy

These should describe why you’ve chosen to serve these customers in

this way, the evidence you used to make that decision, and the highest

leverage ways you can increase the value you create and the value you

receive in return.

- Target customer profiles

- Issue trees

- Impact maps

- Opportunity/solution trees

- Hierarchy diagrams

- Causal loop diagrams

- Other bespoke frameworks and models

Once you have these assets, it’s important to constantly refer to

them in presentations, in meetings, when making decsions, and most importantly,

when there is conflict. Communicate when you change them,

and what made you make those changes. Solicit updates from the

organization. In short, make them part of your normal operations and

don’t let them become wallpaper or another cubicle pinup.

A simple heuristic that we’ve found to understand how successful

you’ve been in this communication is to pick a random individual

contributor and ask them to answer the questions answered by these

assets. The better they can do this without referring to the assets, the

better they will be at incorporating this thinking into their work. If

they don’t even know that the assets exist, then you still have a good

deal of work to do.

The alignment and focus these assets create allow for better

deployment of organizational resources, which enables scaling.

Additionally, they redirect the natural tension between product and

engineering. Instead of unproductive interpersonal friction, you can use

creating and updating these assets as a venue for true collaboration and

healthy disagreement about ideas that strengthen the company.