Highland Park, Illinois

CNN

—

The barstool on the far left at Norton’s Restaurant shouldn’t be empty.

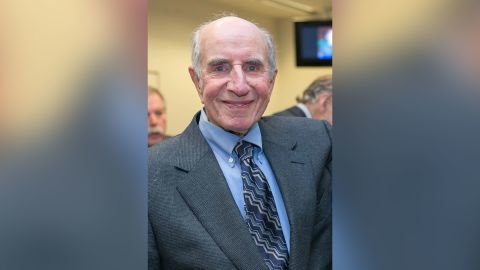

Every week, 88-year-old Stephen Straus filled the seat with his jovial personality, making fast friends with strangers at the fixture in Highland Park, Illinois.

“Norton’s is our version of ‘Cheers’ in Highland Park. Everyone knows your name and all are welcomed with open arms,” said Courtney Smith Weinberg, who lives two blocks away.

“My husband Steven and I had a great night at the bar at Norton’s just a little over a week ago with this amazing man, Stephen Straus. That night we made a new friend! He shared stories about his workout routines, how he still rode a bike several miles a day,” she said.

“The three of us shared laughs together as we ate and drank. I remember how animated and sweet he was … and totally engaged in life.”

Just two days later, Straus and six others were inexplicably gunned down at a Fourth of July parade a few blocks away.

Since then, the restaurant where he brought so much joy has become an epicenter of support for those young and old seeking comfort amid despair.

The blur darting between the kitchen, bar and patio is Israel “Izzy” Velez. He’s part bartender, part server and occasional fill-in manager. But Velez prefers a much simpler job description:

“My job here is to make people happy.”

On this night, his job is needed more than ever. It’s the day after staff and regulars learned of Straus’ death.

It’s also Wednesday – a night when Straus and Velez would typically catch up under the backdrop of the Chicago sports paraphernalia covering the blond brick walls.

Velez gazed at the empty barstool where his longtime friend should be sitting.

“It’s hard,” Velez said, growing emotional. “He was a very, very, very nice man.”

But then Velez quickly composed himself. He wanted to give customers a sense of comfort – a friendly refuge from the grief enveloping the city.

“I have to put on my happy face,” he said.

From across the restaurant, he started greeting customers.

“That’s Michael. That’s Bobby,” he said, as he waved toward the opposite corner.

And soon he was off, reconnecting with those who needed a cold Old Style or Corona, a “Norton” burger or a plate of ribs – and the warmth of a familiar face.

Jonathon Levin and his daughter, Becca, wanted to get close to the epicenter of the attack – not to see the overturned lawn chairs and abandoned strollers that littered the crime scene, but to support impacted businesses close by.

“We didn’t know what was open or not. So we literally said, ‘Let’s drive towards Norton’s and see what’s open because everything’s been blocked off,’” Levin said.

“When we saw it was open, we said, ‘We have to come here. We’ve got to support our community. We have to be here.’”

Though Levin has visited Norton’s many times, an eerie feeling washed over him as he got closer to the area where so many lives were viciously taken.

“As a resident, it’s scary. It’s sad. But we’ve got to move on. We’ve got to keep going,” Levin said. “And part of keep going is to hug everybody, support everybody, and encourage everybody one step at a time.”

On Norton’s patio just a few blocks from the massacre scene, Maya Stolarsky is celebrating her 15th birthday.

She lives in nearby Deerfield, but her family has deep ties to Highland Park. Maya’s mother, Amy, grew up here. Her younger sister, Eden, 12, loves going to the downtown pancake house now cordoned off by police tape.

It was near that beloved restaurant where a gunman, perched atop a roof, sprayed bullets from a semi-automatic rifle onto a crowd packed with families.

Tragedy has left Maya hesitant about going to public gatherings – whether a parade, a mall or a concert.

“It would be unsettling,” the teen said. “I would definitely be thinking about it. It would be always in the back of my mind.”

Shortly after Monday’s massacre that also left dozens injured, Amy Stolarsky knew it was time to give her daughters some grim advice about going to public events.

“What did I say?” Stolarsky quizzed her girls at the table.

“To always make sure you have shoes that you’re able to run in,” Maya replied.

Stolarsky never imagined giving her girls that counsel. “It’s a disgusting thing that I felt like I had to say out loud,” she said.

But if a parade packed with families and children can devolve into a scene of carnage, her daughters must be prepared for any scenario.

Eden, the 12-year-old, said she understands the importance of taking precautions. But she’s not going to live her life in fear.

In fact, Eden’s already thinking about going to the Highland Park Fourth of July parade next year – “to be there in the same place and support” the community.

Just a few blocks from Norton’s, a memorial honoring victims of gun violence sits in front of The Art Center.

For weeks, Highland Park residents have walked past the exhibit, which opened last month, and grieved for those senselessly killed across the country.

No one imagined such horror would soon happen at home. But the gruesome attack in the idyllic suburb north of Chicago proved yet again that no American community is immune.

“When you see these things happen, especially with mass shootings, I keep thinking: ‘This one’s gonna be the end. This news will end this cycle,’” Stolarsky said after Maya blew out the candle on her birthday sundae.

“And it hasn’t happened yet. I’m still waiting for that to happen.”