Attendance Works based its “alarming” estimate on 2021-22 attendance data it has from four states where chronic absenteeism doubled from pre-pandemic levels: California, Connecticut, Ohio and Virginia. “Given the diversity of these states, this offers evidence that chronic absence has at least doubled nationwide,” Chang wrote in a Sept. 27, 2022 blog post.

It may be a full year before we will have national data on student absences during 2021-22 from the U.S. Department of Education. The department only recently posted data from the 2020-21 school year, which showed that 10 million students were chronically absent. That was 2 million more than before the pandemic.

Attendance Works disputes these official figures. Chang points out that five states reported a decrease in chronic absenteeism – an improvement in student attendance – during some of the worst days of the pandemic. “I don’t think so,” said Chang. “That’s got to be an undercount.”

For example, Alabama reported that more than 15 percent of its students were chronically absent in the three years before the pandemic, but in 2020-21, the state reported that its attendance rates had dramatically improved with only 11 percent of its students chronically absent. (A research group at Johns Hopkins University, the Everyone Graduates Center, downloaded data on each state’s absenteeism from the Department of Education website, ED Data Express, and shared it with Attendance Works, which, in turn, shared it with me.)

Some states did not require taking daily attendance in 2020-21. Alabama, the example I cited above, was one of 11 states where taking attendance was up to the discretion of local officials. If attendance isn’t taken, then absences aren’t recorded.

Other states admitted to very high absenteeism levels in the federal 2020-21 data. More than 30 percent of students were chronically absent in Arizona, Nevada, Kentucky, New Mexico, Oregon and Rhode Island.

The federal 2019-20 attendance data appears to be even less reliable. During this first year of the pandemic, the number of chronically absent students decreased in almost every state and for the country as a whole, dropping from 8 million to 6 million students. “This unlikely outcome very probably reflects the fact that most districts stopped taking daily attendance once school buildings closed,” Chang said.

By the fall of 2021, many schools were supposed to reopen as usual, expecting students to come every day. However, new COVID variants swept through communities, forcing fresh quarantines and causing many teachers to miss school too.

“The timing of the Delta and Omicron variants was extremely detrimental for attendance,” said Chang, explaining how the rocky start of the school year made it harder for many children to get into a regular routine and keep up if they missed core concepts in the fall. “Students who missed too much school in the first month of school were more likely to be chronically absent for the remainder of the year,” she said.

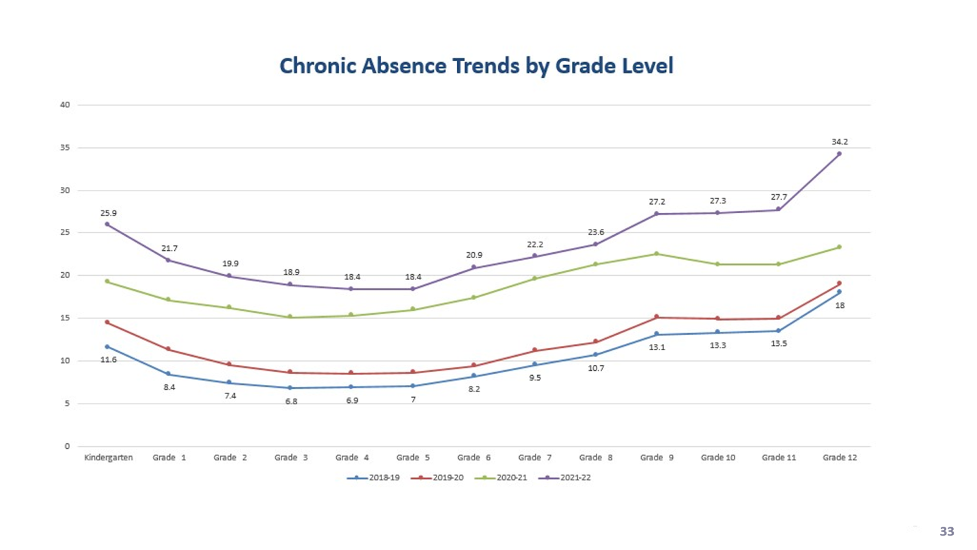

Connecticut, a state that has a reputation for keeping rather accurate attendance records, shows that chronic absenteeism was worst among older high school students and the youngest elementary school students in kindergarten. Still, the 2021-22 absenteeism rate more than doubled for students of every age.

Absenteeism in Connecticut rose sharply for students of every age in 2021-22

Solving chronic absenteeism isn’t easy and involves building human relationships among teachers, parents and students. Chang says that scheduled teacher visits to families’ homes are a “proven strategy.” She also recommends advisory groups for middle and high school students to build connections with faculty. And she suggests that elementary school students be assigned the same teacher for more than one year, a practice called “looping” in education jargon, to build longer lasting relationships. More of her thoughts on what schools can do to address chronic absenteeism are in a blog post she wrote for the Learning Policy Institute on Sept. 28, 2022.

This story about chronic absenteeism was written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.