Maria called me one August day to come and visit her and her fig trees. Originally from Italy, Maria is very short, very sturdy, and 80-something years old, and soon we were also looking at her chestnut trees, Romano beans, broccoli rabe, and more plants. As I was getting ready to leave, she proffered, in her thick, Italian accent, “You wanna some o’ my peaches?” The peaches looked small, fuzzy, a bit greenish, and speckled with brown spots. Still, it was an offer I couldn’t refuse, even if she did refuse my offer to climb her rickety wooden ladder to fill a small basket. That basket she filled held some of the most flavorful peaches I’d ever eaten. To savor peaches and nectarines at their best—drippy, aromatic, and bursting with flavor—you must raise them yourself. The trees never grow large and are ornamental with their showy pink blossoms and lustrous, drooping leaves. They bear fruit quickly, often in their second year.

Although the botanical name (Persica) implies origin in Persia (modern-day Iran), peaches are actually native to China. Long ago, peaches were carried westward, through Persia, on to ancient Greece, and then to Rome. Romans spread the cultivation of the peach throughout their empire. Seeds were brought to America in the 16th century, where they found a welcome reception. Native American tribes such as the Havasupai in the Southwest soon began cultivating orchards of peaches, and in the Southeast, peaches even formed wild stands (called “Tennessee naturals”).

Types of peach and nectarine varieties to grow

Over the years, the range of nectarines and peaches available to gardeners has expanded to include different flesh colors and various shapes. Most people agree, however, that regardless of appearance, most taste similar to the classic favorites.

Tips for growing peaches and nectarines

Nectarines and peaches are practically the same fruit, differing by only a single gene. It’s not uncommon for a branch on a peach tree to mutate and start bearing nectarines, and vice versa.

Basics of growing peach and nectarine trees

- Select a disease-resistant type and one hardy to your specific zone.

- Space trees 10 to 12 feet apart; some dwarf varieties can be spaced closer.

- Select a site in full sun with fertile, well-drained soil. Learn how to make soil more fertile here.

- Prune yearly for the best harvests.

- Be vigilant about pests and diseases; treat with organic sprays or biological deterrents if necessary.

Choose a site carefully, and watch out for pests

To keep your tree healthy, productive, and bearing the best-quality fruit, proper site selection is key. Peaches and nectarines bloom early in the season, so the ideal site is one that does not warm up too early in spring. Also critical to success are full sunlight, perfectly drained soil, and summer warmth.

Peach or nectarine growing is a chancy proposition in less-than-ideal sites. Still, flavorful peaches and nectarines are such a treat that resigning yourself to occasional—or more than occasional—crop failures may still make planting the tree worthwhile. (I’ll settle for two out of five good years.) And anyway, the trees are beautiful in bloom in spring and then pretty all season long; in good years, their fruit makes them even prettier.

How to fight off insects that like peach trees

Insect pests, unfortunately, love peaches and nectarines almost as much as we do.

Plum curculio

East of the Rocky Mountains, plum curculio, an insect that damages developing fruit and leaves behind a telltale crescent-shaped scar, is common. Injured fruit usually drops or becomes susceptible to disease. Curculios are mostly active during the six-week period beginning around when the petals begin to fall. Keep curculios at bay by spraying three layers of Surround before bloom, and then renew the spray every seven to 10 days (more frequently after it rains) throughout that six-week period. Another option is to hit the limbs or the trunk of the tree with a padded mallet every morning to jar the curculios off the fruit. Spread a sheet or tarp on the ground underneath the tree to catch them and to provide an easy means for disposal. Keeping poultry, which eats curculios, beneath the trees also offers some control.

Oriental fruit moth

Oriental fruit moth is another insect pest that attacks peach and nectarine fruit, leaving a large hole where it enters. This insect also bores into young stems, causing them to wilt at their tips. It can be controlled by mating disruption on plots larger than 3 acres. The mating-disruption technique floods the air in an orchard with Oriental fruit moth pheromone, preventing males from finding and mating with females. The Macrocentrus ancylivorus parasitoid wasp, which is native to northeastern portions of the United States, is a known enemy of the moth and will often help control outbreaks also. Spraying Surround, Entrust, or Bt can be effective, although wiping Surround residue (edible but disconcerting) off the skin of a fuzzy peach is challenging.

Tarnished plant bug

Especially in the Southeast, catfacing of fruit can be a problem. These sunken, corky lesions are caused by plant bugs, such as the tarnished plant bug. The insects live among weeds and plant debris, so clean up areas adjacent to trees in addition to spraying, if necessary.

Treat for diseases to get the best harvest

Brown rot

Fruit that becomes covered with a fuzzy gray fungus is infected with the brown-rot disease. Infected fruit, called mummies, darken, shrivel, harden, and often remain hanging on the tree. Remove all mummies from the ground and the tree, because they are a source of the next year’s infections. The disease also attacks twigs, so prune off and dispose of twigs that show the dark, sunken cankers from brown rot.

Brown rot is one more reason for thinning peach and nectarine fruit. A few peach varieties are resistant, including ‘Early Redhaven’, ‘Garnet Beauty’, ‘Harbrite’, ‘Harcrest’, ‘Harrow Beauty’, ‘Glohaven’, and ‘Elberta’. Nectarines are generally more susceptible to brown rot than are peaches, but ‘Red Gold’ and ‘Midglo’ have some resistance. Spraying copper or sulfur around the time of bloom and again before the fruit begins to ripen also helps control brown rot.

Bacterial spots

Dark spots pitting the surface of fruit are symptoms of bacterial spots, another disease more prevalent in moist climates, such as those of the eastern United States. Besides spraying copper during dormancy and in spring, choosing resistant varieties also can limit this disease. ‘Candor’, ‘Earliglo’, ‘Harbelle’, ‘Harbinger’, ‘Redskin’, ‘Redhaven’, ‘Harrow Diamond’, and ‘Harrow Beauty’ are peaches with some resistance; ‘Mericrest’, ‘RedGold’, and ‘Midglo’ nectarines have some resistance. The bacteria overwinter in dark, gummy branch tips and diseased twigs; prune them away when you notice them to help reduce future sources of infection.

Peach leaf-curl disease

If the leaves on your peach tree are reddish, puckered, and curled, peach leaf-curl disease is the culprit. Again, planting resistant varieties (‘Elberta’, ‘Redhaven’, and ‘Candor’, to name a few) and spraying copper help limit the disease. Cold winters kill the fungus.

Bark cankers or borers

If large branches or entire trees are wilting, suspect bark cankers or borers. Cankers are caused by a combination of factors, including wounds and winter-cold damage, the latter the result of lack of cold hardiness or late fertilization. Borers are insects that generally attack weakened trees or trees that have already had their bark damaged, as by lawn mowers or cankers. Kill a resident borer, if already present, by jabbing a stiff wire into the hole in the bark to the borer’s residence. The beneficial nematode Steinernema carpocapsae is a borer killer, and Entrust or Surround sprays are effective against borers. Also, prune off and dispose of twigs with canker disease.

How to harvest peaches and nectarines

“If you don’t like my peaches, baby, don’t shake my tree” goes an old blues tune. It used to be that you just shook your tree to get ripe peaches (or nectarines) to drop. Back then, though, these fruits were mostly used to make brandy and to feed pigs. Some commercial peaches and nectarines are still harvested by shaking the trees mechanically, but for the best fresh eating, more finesse is needed.

When to pick peaches and nectarines

Before picking, wait for the background color to turn yellow on yellow varieties (which include Saturn varieties) and pale green, almost white, on white varieties. The fruit should also have softened (less so for some of the newer, firmer varieties). Cradle the ripe-looking, perhaps softening, fruit in the palm of your hand, give it a twist and a lift, and off it should come. Some varieties release more easily than others. The final and best part of the ripeness test is to take a bite.

Note: Not all fruit will be ripe on any tree at the same time. Plan on three or four pickings over the course of a couple of weeks.

How to prune your peach tree

You will need to prune your peach or nectarine tree every year. To promote rapid healing of pruning wounds and to make it easy to notice and remove branches injured by winter cold, prune as soon as possible after the tree awakens while the tree is in bloom.

Stimulate new growth

Peach and nectarine trees bear only on one-year-old stems, so annual pruning, which prompts new growth that season for fruit-bearing shoots the following season, is a must. It is also important because it thins fruit, especially if you want the biggest and best-tasting peaches and nectarines.

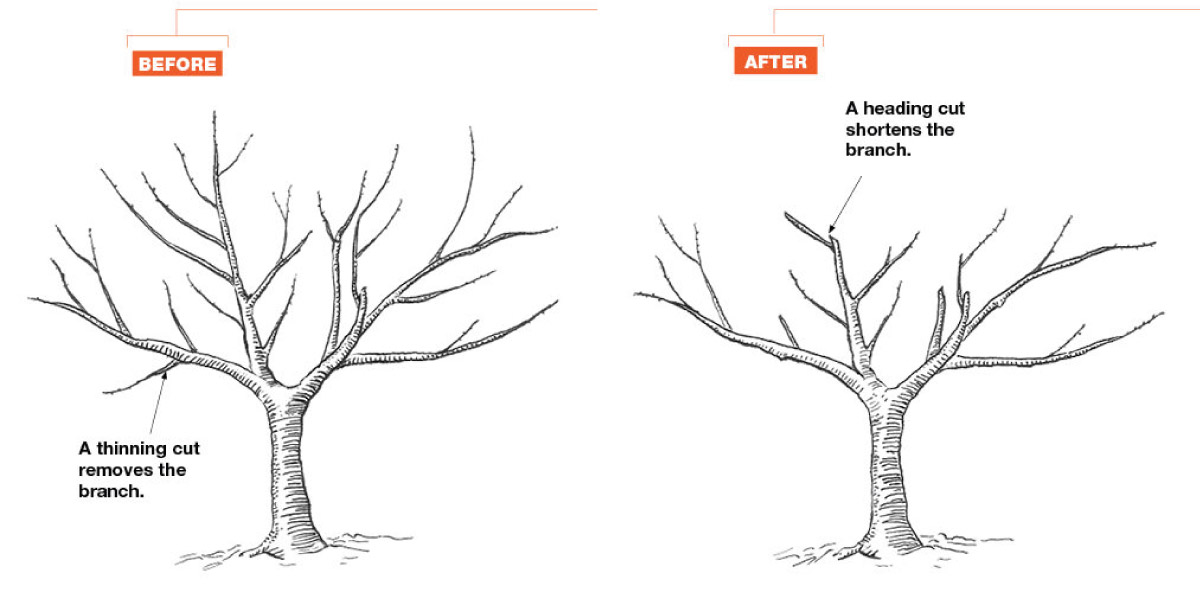

Use a combination of heading and thinning cuts

Invite light and air into the canopy by removing vigorous upright stems, thinning remaining stems, and occasionally cutting back stems into two- or three-year-old wood. Cut back drooping stems as well as very short stems, because they typically produce small fruit.

Strive for an open, airy look

The combined effects of pruning and fertilizing should stimulate 3 feet of new growth on young trees and 18 to 24 inches of new growth on mature trees. When you’ve finished pruning a peach or nectarine tree, you should have removed enough wood so that a bird could fly right through the tree without touching any of the branches.

Lee Reich is a soil scientist and the author of Landscaping With Fruit and Grow Fruit Naturally.

Photos, except where noted: FG staff