Public four-year colleges, by contrast, charge far higher tuition and ultimately spend more than double their state and local funds on their students. Flagship universities attract big donors and can dip into their endowments. “They can still provide a much better education,” said Laderman.

As an aside, I was struck by how much less we as a nation spend on public higher education than we do public school for younger students. Per pupil funding of kindergarten through high school students averaged $15,711 during the 2019-20 school year, according to the most recent data from the Department of Education. Then again, it makes sense for the government to spend more on children’s education which is mandated by the state. College is optional.

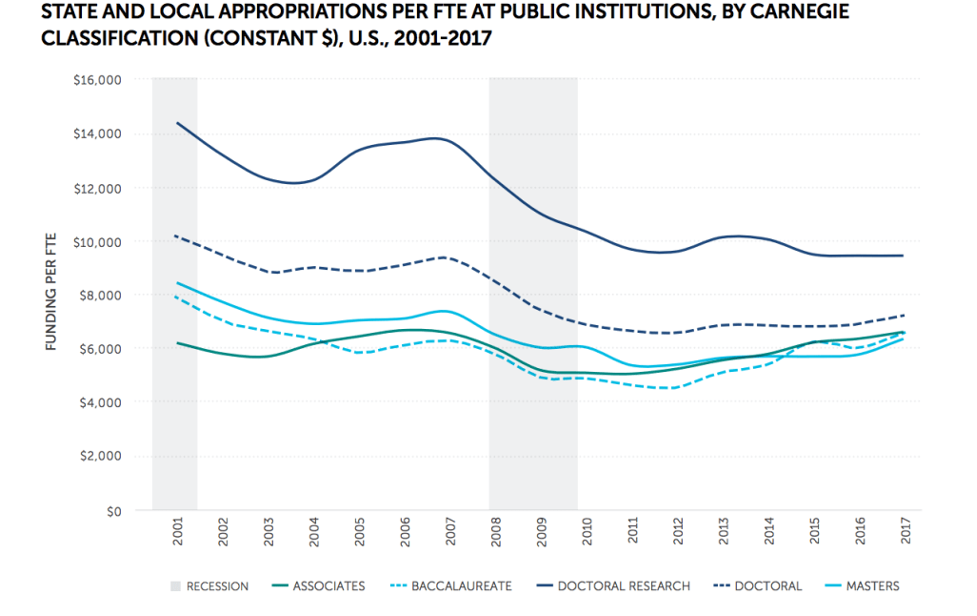

Lawmakers have historically funded public four-year institutions that confer bachelor’s and graduate degrees, such as the University of Texas, more generously than two-year colleges, such as Austin Community College, which award associate degrees and educate more than a third of undergraduate students across the country. When the 2008 recession hit, both community colleges and four-year universities alike were hit with big budget cuts.

As the economy recovered, however, state lawmakers restored funding to community colleges, which positioned themselves as places for blue-collar workforce training. In addition to appropriating more money directly to two-year colleges, lawmakers created many new free community college programs and scholarships, which now operate in hundreds of cities and counties and statewide in almost 30 states. By contrast, a conservative backlash against “liberal” academics tamped enthusiasm for funding increases at more elite four-year universities.

Community colleges also gained from regional real estate booms, which increased property taxes that flow to two-year colleges.

Funding for community colleges, already on the upswing, then surpassed that of four-year universities during the pandemic. State lawmakers had discretion over how to spend a portion of their federal stimulus money and steered a big chunk to community colleges. Some states dug even deeper into their own pockets. Washington, for example, increased its funding of community colleges by 27 percent in 2021, as it introduced a free community college program. By comparison, the state boosted funding of its four-year colleges by 6.5 percent that year.

Ironically, some of the increase in per-student funding was also driven by misfortune. Community colleges hemorrhaged 827,000 students during the pandemic as young adults chose work over school. Some government funding is tied to the numbers of enrolled students but some isn’t. With fewer students, there was more of that untied funding to spread among remaining students.

Laderman cautioned, however, that this aspect of the increase was not a boon for community colleges. They still had to cover many of the same bills as they had before the students left, from faculty salaries to custodians and electricity. Many are struggling financially.

Per student funding would have gone up even without the decline in student enrollment at community colleges. Laderman calculated that state and local education appropriations per community college student would have increased by half as much, or 7 percent, if enrollment hadn’t declined.

It’s unclear how higher education finance will fare going forward. If a recession hits and unemployed adults return to school, that could increase funds for community colleges. But lawmakers may also be pressured once again to cut funding if tax collections run dry.

This story about community college funding was written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.