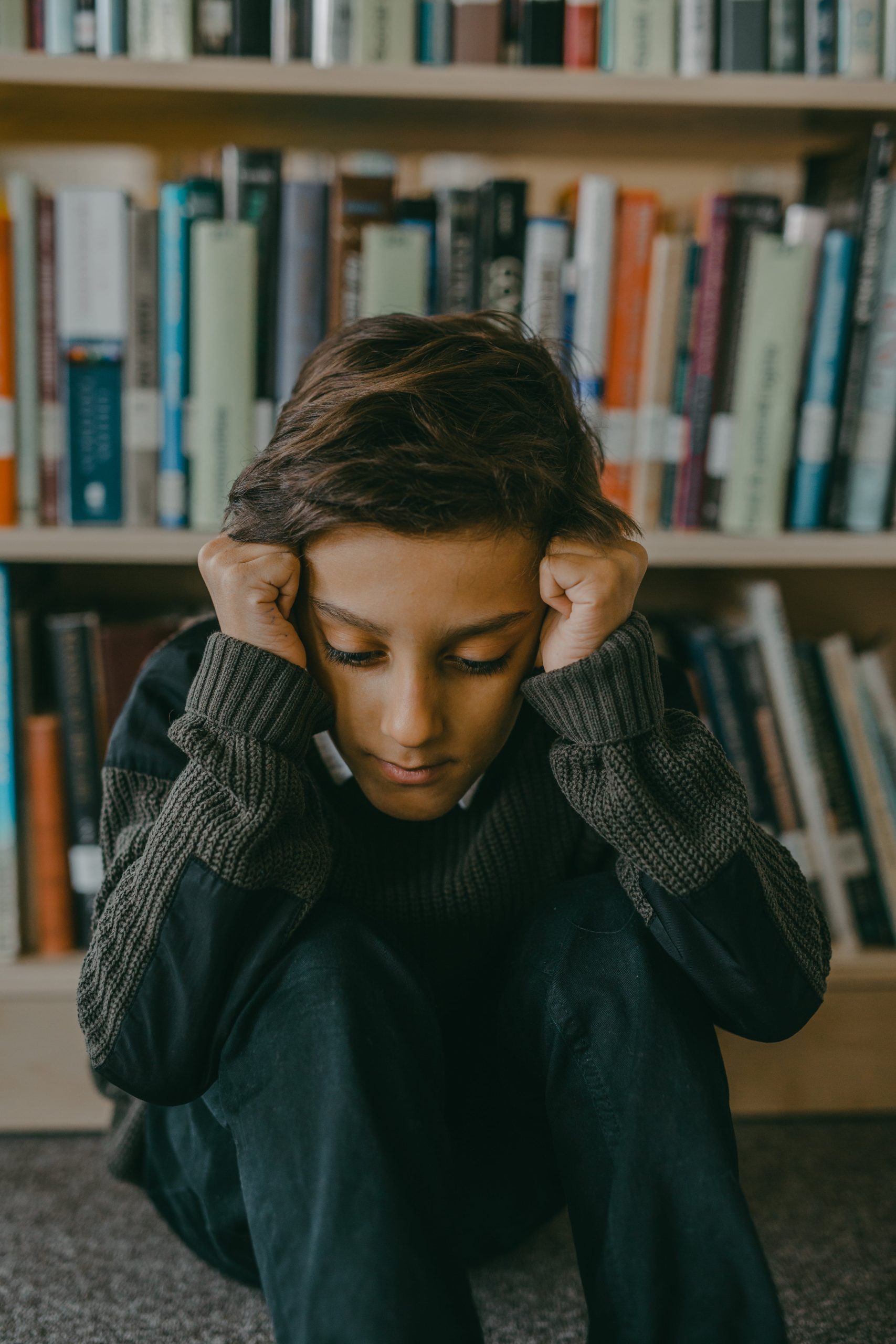

- Researchers are reporting that stress early in life can contribute to cardiometabolic diseases in adulthood.

- They say that’s because high levels of stress hormones may contribute to heart disease.

- Experts say there are a number of ways parents can help children understand and deal with stress.

Stress in adolescence and early adulthood may contribute to the development of cardiometabolic diseases later in life, according to a studyTrusted Source published today in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

To reach their findings, researchers looked at the health information of 276 participants from the Southern California Children’s Health Study from 2003 to 2014 and a follow-up assessment from 2018 to 2021.

The stress participants felt was measured using the Perceived Stress Scale, with questions about thoughts and feelings during the previous month. Assessments were done in three life stages: childhood (average age of 6 years), adolescence (average age of 13 years), and young adulthood (average age of 24 years).

In early childhood, parents provided information on their child’s stress levels. During adolescence and adulthood, the responses were self-reported.

The researchers categorized participants into four groups:

- Consistently high stress

- Decreasing stress

- Increasing stress

- Consistently low stress

The scientists used six different markers to determine a cardiometabolic risk score in young adulthood:

Participants received one point for markers above the normal range. The scientists did not use BMI in calculating the risk score as the body fat percentage and the android/gynoid ratio provided a comprehensive assessment.

End scores ranged from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating higher cardiometabolic risk factors.

Details from the children stress study

The researchers found that adults with high perceived stress, particularly those who indicated high stress levels beginning in adolescence, might be more likely to develop cardiometabolic risk factors as young adults. For example, higher perceived stress is associated with higher neck artery thickness, a blood vessel injury, and hypertrophy marker that could indicate atherosclerosis.

“This study underlines the idea that stress reduction should be a component of our public health strategy,” said Dr. Sameer Amin, a cardiologist and the chief medical officer at L.A. Care Health Plan who was not involved in the study.

“As we have all suspected, high perceived stress can lead to lifestyle choices that worsen cardiometabolic health. When we do not cope with our stress, a healthy diet and regular exercise often fall to the wayside,” Amin told Medical News Today.

Experts say the findings suggest that promoting stress-coping strategies early in life might reduce the risk of developing cardiometabolic diseases as adults.

“For quite some time, we have known that stress can increase the risk of cardiovascular sequalae such as high blood pressure, heart attack, and congestive heart failure,” said Dr. Hosam Hmoud, a cardiologist at Northwell Lenox Hill Hospital in New York who was not involved in the study.

“This paper sought out to quantify perceived childhood, adolescent, adulthood stress and the relation to cardiometabolic risk factors such as blood pressure, obesity and the narrowing of a crucial artery that supplies blood to the brain-the carotid artery,” Hmoud told Medical News Today. “Interestingly, increased perceived adolescent stress led to higher rates of obesity while adults had higher levels of blood pressure and carotid initima thickness. Whether these cardiometabolic risk factors lead to higher rates of stroke, heart attack, and/or congestive heart failure have yet to be elucidated.”

“There are some nuances to this paper that must be kept in mind. The subjectivity of perceived stress and lack of factoring in familial inheritance could confound the results of the paper,” Hmoud added. “It would’ve been interesting to link blood levels of HS-CRP, a known marker of inflammation, with said outcomes. More research is needed to better understand how stress impacts our body from a cardiometabolic standpoint.”

Why stress can lead to disease

“The study did not investigate the reasons why stress in childhood might affect someone’s health at age 40,” noted Dr. Andrew Freeman, a cardiologist at National Jewish Health who was not involved in the study. “If I needed to hypothesize, this is likely because if someone has a history of chronic stress – going back to childhood – they could have maladaptive ways of dealing with stress.”

“There could be a million reasons why the 40-year-old has certain health conditions, but habits persist, and someone who has trouble dealing with stress as a child probably has trouble dealing with stress as an adult,” Freeman told Medical News Today.

“The brain and body are still developing during childhood and adolescence, and stress can disrupt these processes,” said Dr. Daniel Ganjian, a pediatrician at Providence Saint John’s Health Center in California who was not involved in the study.

“Chronic stress can lead to changes in stress hormone levels, inflammation, and other biological factors that increase the risk of disease. Children and adolescents may have fewer coping skills and resources to manage stress effectively,” Ganjian told Medical News Today.

“It’s also important to note that while this research highlights the potential negative effects of chronic stress, it’s not all doom and gloom,” he noted. “Resilience is a key factor in how people cope with stress and there are many things that can be done to build resilience in children and adolescents.”

Originally Posted in Medical News Today

By Eileen Bailey on January 17, 2024 — Fact checked by Jill Seladi-Schulman, Ph.D.