CNN

—

When Ram moved to the Boulder Walk neighborhood just southeast of Atlanta five years ago, it felt like finding a hidden gem: It was a diverse, affordable and family-friendly community just steps away from the local high school, bordering a forest but still a short drive from the big city; perfect for her family of five.

But she hasn’t been able to get used to hearing the daily sprays of gunfire.

“When I first moved here, it increased my anxiety,” Ram, who did not want her full name used due to privacy concerns, said. “It messed up my nerves.”

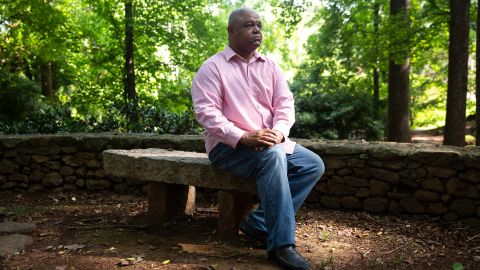

The sound comes from a nearby Atlanta police firing range. It’s unnerving, residents from several nearby neighborhoods told CNN. Worse, they worry it’s just a glimpse into what could come when local officials begin building a massive police and fire training center in their backyards. “I absolutely want the police to be well-trained,” said Joe Santifer, who lives in another neighborhood, roughly a mile away from where the facility is slated to be built. “But if they’re not being good neighbors now, what will give us the confidence that they’ll be good neighbors in the future?”

The expected $90 million, 85-acre center, announced and approved by the city of Atlanta last year, will include a shooting range, mock city and burn building, among other facilities. The Atlanta Police Foundation says the center is needed to help boost morale and recruitment efforts, and previous facilities law enforcement has used are substandard, while fire officials now train in “borrowed facilities.” The police foundation, a nonprofit established in 2003, helps fund local policing initiatives through public – private partnerships. Among those sitting on its board of trustees are leaders of UPS, Wells Fargo, The Home Depot, Equifax and Delta Air Lines.

But the plan has been met with fierce resistance from a community still reeling from monthslong demonstrations protesting police brutality and racial injustice. Some locals say the city’s announcement blindsided neighbors and the development process since has largely been a secretive one with limited input from the most affected communities.

For others, the facility poses environmental concerns at a time when the deadly impacts of climate change have become hard to ignore: The training center would carve out a chunk of forested land Atlanta leaders previously seemed to agree to preserve, though the city says officials are committed to replacing trees destroyed in construction.

Activists determined to stop the project have camped out in the forest’s trees and, despite a permit which could soon signal the start of construction, say they have no plans to leave.

Atlanta and then-Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms were in the national spotlight in 2020 as protests erupted across the country over police killings of Black people, including Rayshard Brooks, a Black man fatally shot in the back by Atlanta police.

The city’s police chief resigned and Bottoms denounced the “chaos” she said was unfolding on the city’s streets, adding she was trying to strike a “tough balance” between criticizing police officers and supporting the ones who protected the city.

In the spring of 2021, following mounting pressure over a demoralized police force, Bottoms announced plans to build a new police training academy in an unincorporated part of neighboring DeKalb County on a controversial parcel of land owned and used as a prison farm by the city for much of the 1900s, sprawling across more than 300 acres. Prisoners there were subject to harsh punishments and bleak conditions, including poor sanitation and nutrition and overcrowding, according to the Atlanta Community Press Collective, a local group of researchers and writers.

“We knew that (the training facility) was a direct response to the uprisings that took place in 2020,” said Kwame Olufemi, of Community Movement Builders, a Black member-based grassroots organization opposing the project.

The site of the proposed project, the Old Atlanta Prison Farm – where graffitied ruins now sit entwined with weeds and vines surrounded by forested land – is a “cultural landscape of memory,” say local advocates, who have long called for it to be turned into a park and memorial.

It’s also less than half a mile away from a tributary of the South River, which is one of America’s most endangered, according to nonprofit conservation group American Rivers. That’s a result of decades of neglect and pollution the area, which is overwhelmingly Black, has endured, local advocates say.

In 2017, a report authored by Atlanta’s city planning department which envisioned the prison farm as a key part of a larger effort to protect green spaces around the river was adopted into the city charter. It felt like a “unanimous promise” from city leaders to protect the land, said Joe Peery, with local volunteer group Save The Old Atlanta Prison Farm.

But in September 2021, after hearing roughly 17 hours of public comment – the majority of which was against the training center – the Atlanta City Council approved a ground lease agreement with the Atlanta Police Foundation, allowing for 85 acres of the prison farm site to be turned into the training facility while the other 265 is slated to be preserved as greenspace. (For comparison, the NYPD’s training academy is a roughly 32-acre campus; the LAPD training campus is about 20 acres.) Andre Dickens, Atlanta’s current mayor, was among the council members who voted for the lease.

“Everybody was floored,” said Jacqueline Echols, board president for the South River Watershed Alliance, an organization working to protect the river. “Just in 2017 they’d said this would be a park and a community investment.”

Though the land is in unincorporated DeKalb County, it’s long been owned by the city, and residents in the surrounding area don’t have a say in city elections or vote for the leaders who made this decision. “It was kind of foisted upon us,” Santifer, who lives in Glen Emerald Park, said. “That’s part of the issue: the lack of transparency, the lack of engagement with this community because frankly, they know the community doesn’t want it.”

The police foundation has said the city went through an “exhaustive review of its properties” before selecting the site, adding it is the only one owned by Atlanta big enough to accommodate the two departments’ needs. And even if another privately-controlled site was identified, the foundation has said, preparing it for development would take “decades and present taxpayers with an unwarranted financial burden.”

City spokesperson Bryan Thomas told CNN the prison farm site was “a pragmatic choice, given its adjacency, its ownership by the City and its former and continued use” by Atlanta’s police and fire rescue departments.

Other sites were explored over several years, Thomas said, adding the city engaged with a group of designers, architects and engineers about what a “first-rate training center” would require. The group eventually focused on the prison farm site since it has previously hosted training facilities, like the firing range, Thomas added.

CNN also reached out to the police foundation for comment.

After the September 2021 vote, Bottoms said she was aware of widespread opposition to the facility, but the city did not have any other site options to choose from, according to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. The center was a move to support the city’s fire and police officers “while also focusing on sensible reform,” Bottoms, who did not run for reelection, said in a September 2021 news release.

The White House had no comment from Bottoms, who serves as senior adviser to the President for public engagement.

Perhaps the loudest voices of opposition come from activists and organizers who have dubbed the plan “Cop City” and called on Mayor Dickens to cancel the lease.

“Tree sitters” and other members of the “Defend the Atlanta Forest” movement built shelters in trees to prevent the facility’s construction and have also called attention to the forest’s history, saying a police center will continue a legacy of oppression on the land. Before it was a prison farm, White settlers established slave-based plantations in the area after forcing off the Muscogee Creek tribe, according to anthropologist Mark Auslander. Forest defenders refer to it today by its Muscogee name, Weelaunee Forest, as a nod to its original inhabitants.

Members of the movement have been accused by local officials and some neighbors of using violent tactics in related opposition efforts, including allegedly setting a tow truck on fire. In May, eight protesters were arrested after a Molotov cocktail was allegedly thrown at police as authorities tried to remove them from the area, according to CNN affiliate WSB. But it did not deter their efforts. The Defend the Atlanta Forest Twitter account posted a letter in August it said was from a tree sitter. “I’ll be here keeping up the struggle,” the letter said. “My question to the (Atlanta Police Foundation) is: When will you give up?”

The Community Movement Builders group, which also opposes the plan, would have liked to see the financial resources instead be put toward mental health, food and housing programs for south Atlanta communities, according to Olufemi.

Taxpayers will fund about $30 million of the facility’s cost in total, with the rest coming from private philanthropic and corporate donations, the city has said. Among those backing the center is the Atlanta Committee for Progress, a partnership between the mayor and the city’s top business, civic and academic leaders. Its former chairman, Alex Taylor, Chairman and CEO of Cox Enterprises, led the initial private funding campaign for the center at then-Mayor Bottoms’ request. (Cox owns The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, the city’s major daily newspaper.)

Cox Enterprises spokeswoman Sonji Jacobs told CNN in a statement, “The Atlanta Journal-Constitution has always operated with complete editorial independence, and the newspaper, in its coverage of the police training facility, has repeatedly disclosed that it is owned by Cox Enterprises.”

Atlanta Police Foundation President and CEO Dave Wilkinson wrote in a 2021 Atlanta Journal-Constitution op-ed a surge in violent crime across Atlanta since the summer of 2020 called for “more effective law enforcement,” but the city had struggled to build morale and retain employees in recent years.

Residents who are in support of the facility told CNN they wanted police to be able to train properly and hoped the development would make their communities safer and help spur economic development.

Spence Gould, a marine and resident of the Boulder Walk community for roughly a decade, said he sees the need for a training center. “I want my police force very well-trained, I want them to have all the resources that they need,” Gould told CNN. “But I also see the (Defend the Atlanta Forest) concerns because we are really wrecking the planet.”

Once the foundation has a land disturbance permit (which is still under review, according to DeKalb County) and construction begins, a fence will be put up around the site and anyone on the property “will be arrested,” Wilkinson told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in March.

Construction is expected to begin in the late fall and the first phase of the facility is expected to open before the end of 2023, the city spokesperson said.

Before the mayor’s sudden announcement, the prison farm site had been a key centerpiece in another vision: the South River Forest.

The forest is a 3,500-acre network of connected green spaces across parts of Atlanta and DeKalb County, which advocates say is desperately needed. Despite being known as the “city in a forest,” Atlanta has massive disparities in green space, with fewer and smaller parks in predominantly Black areas like this one. And with a population size expected to sharply increase in the coming decades, the benefits the forest can provide – floodplain restoration, habitat expansion and tree canopy protection, among others – will be critical, the Nature Conservancy has said.

In August 2021, more than a dozen environmental organizations, including the Sierra Club’s Georgia Chapter, wrote an open letter to city leaders urging them not to lease the prison farm site to the police foundation, arguing ragmenting the South River Forest will leave surrounding communities vulnerable to adverse impacts, like stormwater flooding – a problem already worsening because of climate change.

“The forest serves as the city’s lungs,” said Nina Dutton, chair of the Sierra Club Metro Atlanta Group. “Forests capture carbon, they clean the air … they mitigate flooding and prevent erosion and they help keep the city cool. Breaking up this area of forest would reduce the amount of forest that’s available to help us in those ways.”

The forest vision could also spur economic development in long neglected areas and reconcile decades of environmental injustice with investment, said urban planner Ryan Gravel. “If you live in a community in the South River Forest, you’re more likely to live within walking distance of a landfill or a prison than anywhere else in metro Atlanta, by far,” he said. “You’re talking about an area that has historically been treated as a dumping ground.”

Thomas, the city’s spokesperson, said training facilities will make up less than half the site, while the rest will be green space open to the public and include walking trails and picnic areas.

Much of the land to be developed has previously been cleared of trees and the parts including forest cover are “overwhelmingly dominated by invasive species,” devoid of thick forest, Thomas added. The Atlanta Police Foundation has committed to replace any hardwood tree destroyed in construction with 10 new ones and replace any invasive species with hardwood trees, the spokesperson added.

But advocates with Save the Old Atlanta Prison Farm argue most of the land has been reforested and reducing the forest in any way would also reduce the economic opportunities for the surrounding communities. “The noise and smoke coming from the Police Training Facility would further erode that impact,” the group has said.

Although the training center will put a dent in advocates’ plans, many are still determined to see the South River Forest come to life. An ongoing initiative by the Nature Conservancy and the Atlanta Regional Commission is collecting community input about the forest’s future and is slated to wrap up in the coming weeks.

“This could be the first step in starting to reverse some of the discrimination that this part of the city has seen over the last decades,” Santifer, who is among the project managers of that initiative, said.

DeKalb County leaders could soon take a vote on a resolution introduced by county commissioner Ted Terry calling for an environmental assessment of the site and a noise study for the proposed center – and asks developers to reconsider the location if their plan cannot satisfy environmental standards. (Atlanta Police Foundation officials have said the center will “be built with 21st century EPA standards and controls.”)

Terry recently said on Twitter county leaders have received more public comment from residents on this issue than any other during his tenure. “All opposed,” he wrote.

Dickens, Atlanta’s mayor, told the New Yorker recently an advisory committee created in the aftermath of the lease approval offered a way for public input on the project. But critics of the group note its members were appointed by local officials and don’t have the power to hold the police foundation and developers accountable to the community’s concerns.

One member was voted out after publishing an opinion piece criticizing the police foundation and project developers for misleading the community and avoiding their environmental due diligence – including by never investigating the possibility of unmarked graves on the prison farm land.

The committee isn’t meant to serve as a watchdog, but rather to make recommendations on changes or adjustments to the development which would benefit surrounding communities, said committee chair Alison Clark. And so far, the foundation has adopted all the group’s recommendations, she added, including relocating the center’s firing range further away from residential areas.

Clark, who has lived in the Boulder Walk neighborhood for roughly eight years, told CNN she is in favor of the training facility. She agrees the area has long been used as a “dumping ground” for unpopular developments like landfills, and hopes the center can help economically lift the area, bring in new vendors and also boost police presence. “At the end of the day, I think that’s a win-win for the community,” she said.

But ahead of the DeKalb County commissioners’ vote, county leaders heard from residents who said the project remained highly unpopular among the surrounding communities and urged for the approval of Terry’s resolution.

“Residents in the area, who are predominantly Black and brown, often low-income, have been left out of the decision-making process and their voices have been ignored,” DeKalb County resident Brad Beadles said during an August meeting, according to a summary posted on the county’s website. “No one should have to be subjected to such clear harmful violations of our environment and our neighborhoods.”

Terry told CNN he is taking more feedback from community members on the resolution and expects a vote on it from the commission next month.